When it comes to new games, there’s a natural assumption among a large swath of the gaming community that anything truly original or interesting has to come with a degree of length and complexity to it. The logic being that if there’s only so much design space in the realm of concise, simple social games, and therefore most new titles in that genre are simply derivatives of those who have come before them – which in turn means that they’re hardly worthy of your attention.

Of course, tell that to Codenames. Or Secret Hitler. Or the litany of other half hour social games that have systematically been praised time and time again in the last few years for being clever, entertaining, and yes, even original.

Well, be prepared to add another name to the list of the worthy with Visitor in Blackwood Grove, the latest title by publisher Resonym. In this game, 3-5 players spend a scant handful of rounds trying to either save an alien’s life…or prematurely end it.

The premise of Visitor in Blackwood Grove is pretty simple: an alien has crash landed on Earth, and big bad government agents are seeking to swarm in to dissect both the ship and the pilot. Mostly because we’re human and that’s what we do. However, they are currently being held at bay by a strange forcefield that seems to allow only a select handful of items through it.

In true Spielberg-ian fashion, the only one able to help this alien before the forcefield fails is a plucky neighborhood kid who is being fed clues by the alien to figure out the secret to the forcefield. If she can properly decode his messages, she’ll be able to slip through and help him repair the ship in time. This isn’t as easy as it sounds, though, because unlike every sci-fi series ever, this extraterrestrial doesn’t speak English. It can only communicate through imagery – and their interpretations thereof.

In short, it’s Mysterium meets E.T, with the entire playthrough taking about 20 minutes.

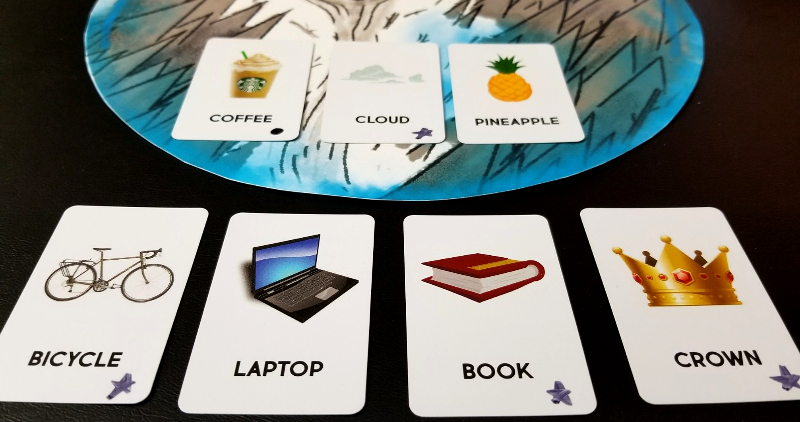

Setup for the game is fairly minimalistic, as nearly the entirety of the game’s decisions revolve around a single deck of cards. Cards like these:

Every one of these cards represents a litany of innocuous and disparate objects, from magic wands, to gold bars, to airplanes, to cherry pie; when the game begins each player will draw a hand of seven. On the surface there is little connecting any of these ordinary items, but your job is to figure out what the correlations are, if any.

How you do that depends on the role you’ve been given. For in every game of Visitor, one player is the Visitor, one is the Kid, and the rest are decidedly non Mulder-like Agents.

The game begins – as you’d expect – at the forcefielded crash site. There, the Visitor must establish the Pass Rule for the forcefield that the Kid is trying to figure out. Using the seven cards in their hand and two additional revealed cards from the deck, the Visitor player must create some kind of secret rule in their head based on the objects available to them. This rule can be practically anything – as long as it pertains solely to the objects themselves. The objective with the Pass Rule is ultimately is to come up with something that the Kid can decipher easily but challenging enough that the Agents won’t immediately be able to guess.

For example, you might come up with ‘things found on a lake’, or ‘things that can you carry’, or ‘things that are green’. And so on.

Simple in concept, this one condition sets the entire game in motion, bound only by the cards available to the Visitor and the player’s creative thinking.

This one decision also strikes at the heart of what makes Visitor in Blackwood Grove so enticing. Its open-ended rule-setting affords you all kinds of freedom when determining what path you want to take, restrained only the 9 cards available to you. When combined with the variety of cards of each playthrough, this gives the game a nearly limitless degree of replayability. What’s more, the Visitor role, much like the ghost in Mysterium or the spymaster in Codenames, is played out with minimal speaking.

In fact, one needs not need to be able to speak at all. While the game doesn’t go so far as to require it, you can technically play Visitor In Blackwood Grove without anyone uttering a single word. Technically. If nothing else, this helps underscore how much of the game tightly focuses on the sharing and extrapolation of visual cue cards over everything else.

Once the rule is decided, the Visitor then specifies whether the two revealed cards are ‘In’, meaning the rule allows it through the forcefield, or ‘Out’, meaning that it does not. Then the Agents take over.

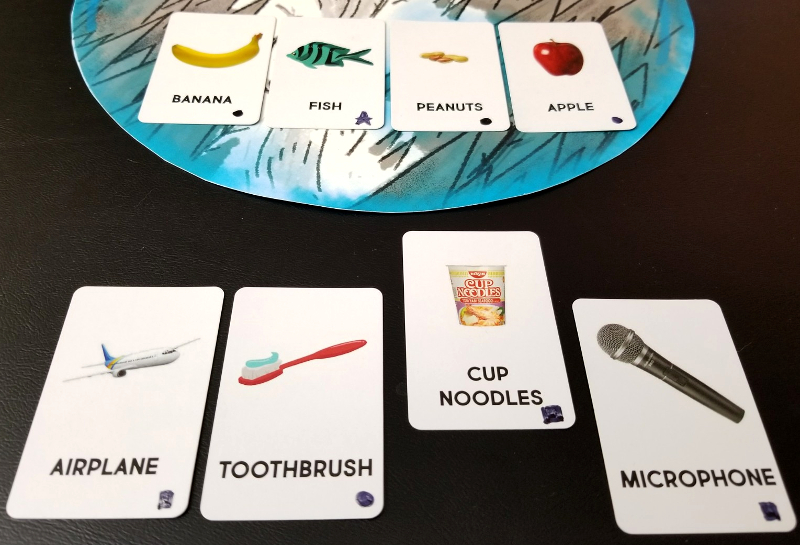

Each round works the same way, with each Agent player taking their turns first. An Agent may either choose to Test a card, or attempt to Prove they know the Pass Rule. To Test a card, the Agent shows a card from their hand to the Visitor, with the Visitor stating whether it’s ‘In’ or ‘Out’. However, since every Agent in the game is out for themselves (seeking the fame and glory that would come with dragging home a little grey man), the card is shown in secret. The Agent keeps that cards to themselves and then draws a replacement.

Proving is a riskier gambit, at least for the Agents. This involves revealing four cards from the deck, and then having to correctly guess whether all four of them are ‘In’ or “Out’. If they’re right, then that Agent wins and it’s curtains for our friendly Visitor. On the other hand, guessing incorrectly adds those four cards to the puzzle for other Agents or the Kid to use in their deduction while also raising the Trust track by 2.

In Visitor, the Trust track represents the growing relationship between the Visitor and the Kid. Every time Trust increases, not only does the Kid get to draw additional cards, but it makes it progressively more difficult for the Agents.

The Agent attempted to guess, assuming (incorrectly) that the answer was ‘things that you eat”.

Prototype Shown

Once every Agent is done, the Kid takes her turn. The Kid works as a team with the Visitor, trying to help them escape. To do that she also has two possible actions: Predict or Prove. Proving for the Kid works the same way as the Agents, with the exception that aside from giving valuable info to the enemy, there is no penalty for being wrong. Predicting involves revealing a card from her hand and guessing whether it’s ‘In’ or ‘Out. If she’s right, Trust increases by 1 and she may press her luck by guessing another card (up to three times). If she’s ever wrong, though, then her turn ends immediately. The Kid therefore has to carefully balance the desire to increase the Trust track, guaranteeing more cards and better odds of success, with ensuring that by doing so she doesn’t provide too much intel to the Agents.

Although you can only take one of two actions in either of these roles, the balance between risk and reward creates some nice lightweight gameplay symmetry. One choice is clearly safer, but slower, while the other is a bigger gamble – and also how you win. This keeps the game easy to learn and understand while also retaining a sense of agency and purpose – something not always easy to do in shorter games.

Finally, each round ends by the Visitor taking their turn. This consists solely of choosing a card from their hand and classifying it. The Visitor never draws additional cards, though, so if they can’t play a card, then time has run out – the Agents crush the defenses and the Men In Black collectively win. This gives the Visitor and the Kid at most around 8 rounds to figure things out. So…no pressure.

Blackwood Grove’s one admitted quirk resides, unsurprisingly, with the Pass Rule. Because so much of the game revolves around the powers of interpretation, it is possible that through the guesses of the Kid or Agents that they win the game based on an entirely different Pass Rule than was envisioned. Yet, in an oddly pleasant way, this actually plays into the game’s advantage. You don’t have to figure out the exact Pass Rule created if your logic brought you to a similarly applicable conclusion. This helps retain the casual and rules-light atmosphere that the game offers without diminishing the enjoyment of it by being forced to guess something that may be too obscure. It can also be quite entertaining if someone points out a relationship between the cards that the Visitor didn’t even see.

By giving players a mix of logical deduction and relation-based visual interpretation, Visitor at Blackwood Grove casually but confidently joins the same family of team-based social games like Dixit, Mysterium, and Concept. It also happens to do it in a fraction of the time, scratching that exploratory itch in under a half hour. Every role provides a different experience, whether it’s guiding the players to the obfuscated solution or racing to be the first to understand the clues before them. It’s impressive just how dynamic the gameplay can be, further illustrating that games can have merit at any weight class. Visitor at Blackwood Grove is both an entertaining game with loads of replayability and an enlightening take on the power of communication. It’s quick, accessible, flavorful, and has that annoying tendency of wanting to shuffle up and play again and soon as its over. If this sounds like something that would interest you, then be sure to beam on over to its Kickstarter.

This project has earned the Seal of the Republic

Photo Credits: Visitor In Blackwood Grove cover and artwork by Resonym.