History has shown us time and again that uniting a fractious country is not an easy task.

As a leader, it’s up to you to decide how to proceed. Is it better to merge opposing factions together by strength of an iron fist or by mediation and diplomacy? Is it more advantageous to lead by a show of force or insight? Will you inspire those to follow you by appealing to anger and fear or providing hope and optimism? Do you motivate by lifting people up, or putting others down?

The manner of how one should guide their people has perplexed men and women throughout the entire course of civilization, from the earliest human tribes to, well, now. From authoritarian despots to transcendental paragons of virtue, the world has seen its share of both the very best and very worst of what leadership is capable of. Within each of us lies the capacity for great compassion – or great malice. For every Ghandi, Mandela, or Lincoln, we’ve had a Genghis Khan, Hitler, and Vlad Tepes.

The manner of how one should guide their people has perplexed men and women throughout the entire course of civilization, from the earliest human tribes to, well, now. From authoritarian despots to transcendental paragons of virtue, the world has seen its share of both the very best and very worst of what leadership is capable of. Within each of us lies the capacity for great compassion – or great malice. For every Ghandi, Mandela, or Lincoln, we’ve had a Genghis Khan, Hitler, and Vlad Tepes.

The question then becomes: if given the chance to rule, which path would you choose?

Such is the question put before you in Path of Light and Shadow, the newest (and largest) game from Indie Boards & Cards. Designed by Travis Chance, Jonathan Gilmour, and Nick Little, this expansive 2-4 player game drops you right into the middle of a land divided. Its peoples are in desperate need of a unifying ruler, and if you play your cards right – along with a little luck – that person could be you. Blending a mix of deckbuilding and area control, players take turns gathering supporters, upgrading their assets, and above all, attempting to regain control of the various territories in the land usurped from your ancestors.

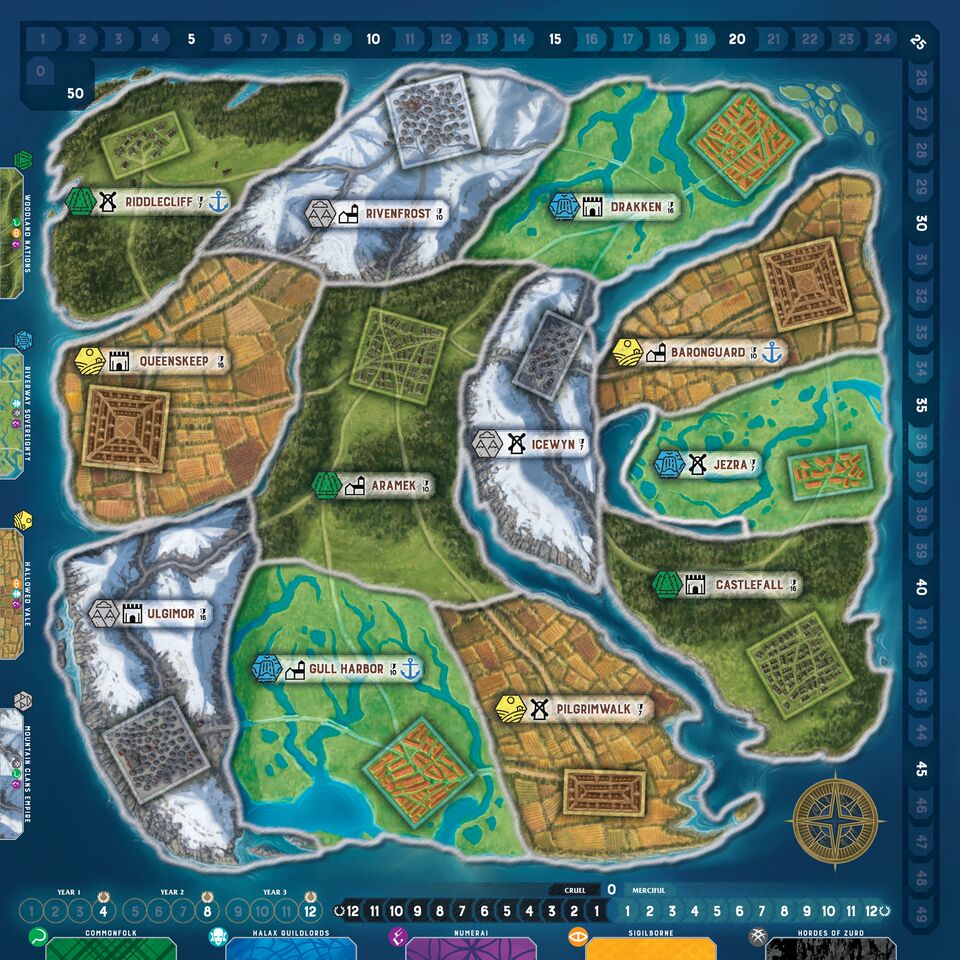

This land, in fact:

Your fractured homeland is divided into twelve provinces: three territories are held by each of the game’s four major factions. Of those, one province is designated a Village, one a City, and one a Stronghold – essentially stipulating how difficult that locale will be to take over. After a scant 12 turns of skirmishing and the securing loyalty of the realm, the player with the most VP will take the throne.

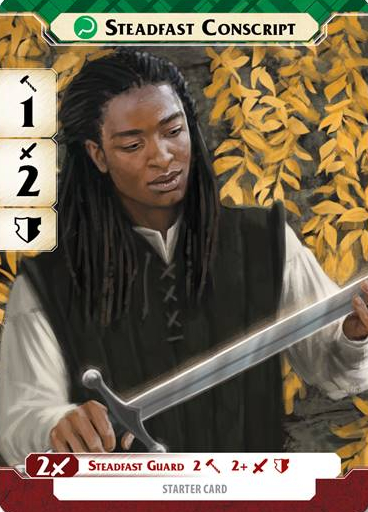

As with most deckbuilders, each game of PoLS begins with a handful of initial cards, providing you with some starting recruits. Because honestly, it’d be a bit sad if you didn’t have any followers in your quest to take the throne. Who would even take you seriously in that case? We’re pretty sure carrying a sign saying, “Have Legitimacy to Throne, Need Army” wouldn’t go over well…

Every card contains a number of traits and abilities, but the most important are their resource values, being Labor and Strength, both of which will help you take various actions throughout the game’s dozen rounds.

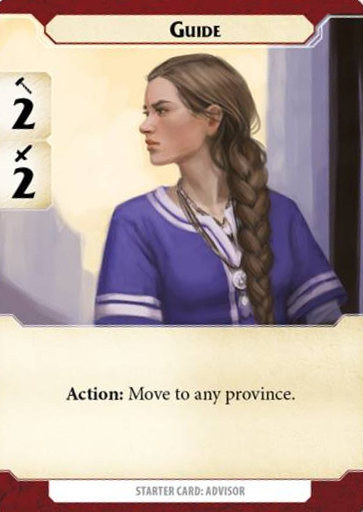

Each player also starts with a random Advisor card – which every good ruler ought to have. Arthur had Merlin, Burns had Smithers. So naturally you should have one too. Each Advisor is a unique card that will aid you strategically throughout the course of the game.

Finally, everyone rounds out their starting deck two cards from the realm faction of the Village province you begin on, which is chosen at the beginning of the game. Then each person draws five cards and the campaign begins.

With only 12 turns to claim dominance, both flexibility and decisiveness are required. The game reflects this by way of offering a variety of actions to take on your turn in whatever order and frequency that you desire – with the exception of Movement to an adjacent territory, which is limited to once per turn. Horses can only move so fast and all.

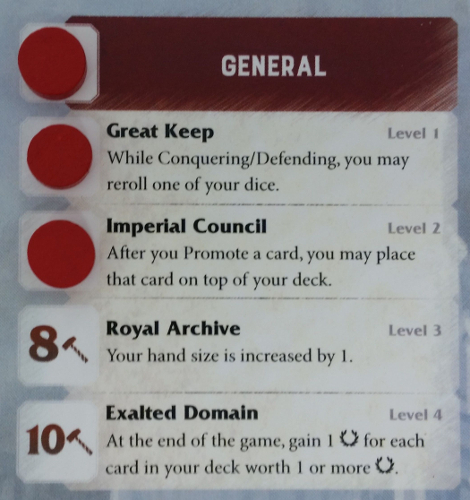

The first notable action is to Build a Structure. Every player starts with a Structure board containing various ability upgrades that you can purchase to flesh out your current strategy. Structures require spending Labor to build and get expensive quickly, with the top tier Structures providing endgame VP – not unlike large structures in Race for the Galaxy or Puerto Rico.

Another major action, and one of the most appealing aspects in Path of Light and Shadow, is the ability to also upgrade or “Promote” your existing cards.

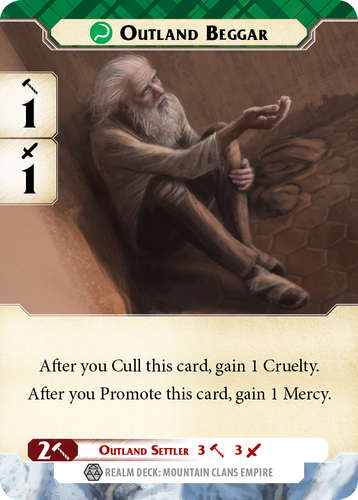

Every base card is capable of being promoted up to twice by paying its requisite costs in either Strength or Labor, depending on the card. Promoted cards have better resource values and generally stronger abilities. These cards added to your deck, replacing their previous version.

More a means to an end than a victory path unto itself, the process of improving individual cards in your deck is advantageous, thematic, and aesthetically satisfying. It provides flavorful significance for a deckbuilder beyond the rote act of trashing one card for something better. What’s more, all of this is reinforced with superb card artwork, bestowing the game with a rich and diverse portrait of the denizens fighting for (and against) your cause.

Sprinkled among the faction decks, though, exist the Numerai, a magical nomadic race who once ruled the land long before pesky humans showed up. Sort of a cross between a shaman and an elf, Numerai cards are more powerful than normal cards, and Promoting them is slightly different. That is, they can only be upgraded once, and it’s done via a random draw. So while it’s almost always a guaranteed improvement, unlike other promotions you’re never quite sure what you’re going to gain in the process. Because magic.

Another familiar action in Path of Light and Shadow is trashing or Culling cards, though this too is done in a notably thematic way. Culling requires playing Strength cards, the total value equates to the number of cards you can remove from your hand and/or discard pile. The catch, however, is that doing so earns you Cruelty points.

Which brings us to the mechanic behind Path of Light and Shadow’s namesake, as well as, ironically, one of its few weak points: the morality track.

Throughout the course of the game you will make decisions that will earn you either Cruelty or Mercy, moving you along the typically grey scale of human endeavor. This appropriately reflects your temperament as a ruler. For example, since every card in your deck represents one of your followers, it makes sense that Culling generates Cruelty, as it means you abandoning (or outright killing) loyal followers to fuel your ambitions. Just as doing the opposite can get you Mercy.

Thus, if you want to max out Cruelty, then get ready to bring out your inner Joffrey. To do the opposite, be prepared to feed every beggar who comes your way.

In reality, however, beyond nailing the flavor ramifications behind it the morality track is mostly used to underscore the type of strategy being taken. 3/5 of the game’s factions encourage you to pick one side and max it out as soon as possible to make cards of that strategy path more powerful. Only one faction flitters with the idea of fluctuating between being good or bad, which means most of the time you’re committing to a single path early on with little incentive to alter course. Which makes it feel slightly underutilized at times.

That being said, the two ends of the spectrum are remarkably balanced…if you’re familiar with the game. While not a criticism, Path of Light and Shadow is a game that undeniably rewards player experience to fully grasp the variety of options available to you; it can take a few playthroughs to fully grasp the depth of possibilities the game contains. The path of Cruelty via culling and attack cards is far more evident to newer players for instance, but the Light side is just as capable at shoring up powerful moves too. It just may take more practice.

Sort of like being a medieval Jedi.

All of these decisions ultimately lead to the purpose behind Path of Light and Shadow’s deckbuilding foundations: conquering the land like a triumphant Caesar. The Conquer action reflects the area control part of the game, whereby you attempt to take ownership of the province your leader is in.

Conquering involves playing Strength cards, with your highest valued card becoming dice. Your goal is to meet or exceed the value of the location’s defenses, plus the defense rolls of the defending player (if there is one). Successful attacks reward you with ownership of the territory and a pair of cards from the realm. Unsuccessful attacks reward you with taunts from the peasant folk.

Which you’re going to want to do as frequently as possible. For all of the game’s well-executed tech trees and deck honing to attain endgame points, the area control nature of this game is inescapable. It is a fight for control of the kingdom. While the game successfully avoids being overly cutthroat, the fact remains that if you do not Conquer, you do not win. Case in point: the bulk of the game’s VP is attained every four turns based on the value of the regions you control.

One notable absence of possible actions, however, is the acquisition of new cards. This is because attaining them in Path of Light and Shadow is partially out of your hands. Aside from Conquering spoils, you always add one card to your deck from your current province at the end of your turn, and for a Mercy point, you may add a second.

In all cases, the card acquired is random, exemplifying that you don’t always get to choose who decides to follow your cause. Some may do it because they believe in the objective while others will entirely for their own self-serving ends. Hence, some cards you get will be desirable and tie into your strategy. Others just become dead weight for your growing entourage.

This leads into what will be the make or break characteristic for many players: Path of Light and Shadow has an unapologetic level of uncertainty to it. This is by design. What cards you gain each turn is unpredictable, just as the inclusion of dice when attacking illustrates the chaotic improbability of war. You could march in with overwhelming odds and lose, or take a long-odds gamble and have it pay off.

With 3 successes from the dice plus 4 remaining Strength from card, it still isn’t enough to scale the Stronghold’s 12-value defenses.

Prototype Shown

There are ways of mitigating the numerous degrees of chance at work, but when coupled with the normal luck-of-the-draw nature already inherent to deckbuilding, it may be enough to give certain players pause. Path of Light and Shadow blends a straightforward-yet-thematic area control experience with a familiar deckbuilding enterprise, but Star Realms this is not. For those who prefer deckbuilders of min-maxing their way into victory, this is not the Path for you.

On the other hand, if you want a visually appealing deckbuilder with a purpose, then you’ve come to the right place.

What makes Path of Light and Shadow particularly intriguing is that while its individual pieces are familiar, the combined effect delivers a robust experience that deviates starkly from your standard engine building deckbuilding affair. It’s accessible but complex, random but rewards committing early to a plan, and every mechanic has a thematic justification of one kind or another.

With limited resources and always less time than you think to achieve your goals, Path of Light and Shadow perpetually tests your leadership mettle by pulling you in multiple directions at once. Utilizing elements of deckbuilding, area control, and even a little civ-building for good measure, Path of Light and Shadow embodies the depth of potential in the Deckbuilder 2.0 genre.

If you think you have what it takes to help retake the throne, then march on over to its Kickstarter and pledge your oath of fealty.

Or money. That’s good too.

Who will you follow?

Photo Credits: Path of Light and Shadow cover and artwork by Indie Boards & Cards; Monty Python by Sony Pictures.