For as long as mankind has been able to stare upwards, we have wondered about the skies above us and the worlds beyond. For generations, countless stories, fables, and myths have evolved out of our ability to simply look up out of awe and curiosity. Yet in all of this, few celestial bodies evoke the kind of response than that of the moon. Our moon. Luna. Earth’s little sibling and closest pal in the grand cosmic dance.

From filling a litany of religious roles to whether it’s made of cheese, we humans have always been fascinated by the moon. We’ve wondered how it controls our tides and how it seems to have a shifting personality throughout the year. We’ve pondered over how it gave us waterbending and turns people into werewolves. We’ve been perplexed about who the man in the moon really is and what he did to get there, exactly.

And once a handful of astronauts touched down on it all those years ago, it reinforced to us that there was a whole universe out there waiting to be explored – once we were ready to make that step.

Well, that day is coming soon, and it’s about to have some pretty commanding real estate prices, thanks to the Luna Mare design firm.

Yes, now that we’ve made viable space stations for research and dumped robots on Mars, the time has come for humans to build a sustainable moon base the likes of which even Robert Heinlein would have admired.

As it happens, that’s precisely what you’re being asked to in Lunarchitects, the inaugural release by Iron Kitten Games. In this tile-snatching, tableau-building game for 1-5 players, each player is as a member of an architectural design team who has been tasked with building a moon base, and you’re all competing architects to get your particular blueprint chosen. To accomplish this, you’re going to need to assemble the right set of modules to make sure your settlement is sustainable and your colonists don’t accidentally go floating out an open airlock. As such, meticulous planning and tactical positioning are essential to victory. No pressure.

At initial glance, Lunarchitects appears to be gearing as a fairly daunting game, replete with four different stacks of blueprint tiles, numerous resource tokens, a mini marketplace, and multiple scoring rounds.

Yet for all of its components, the game is deceptively easy to teach and players catch on quickly. Besides understanding some light tile iconography, the entirety of the game is relegated to a couple short pages of rules, largely thanks to intuitive gameplay.

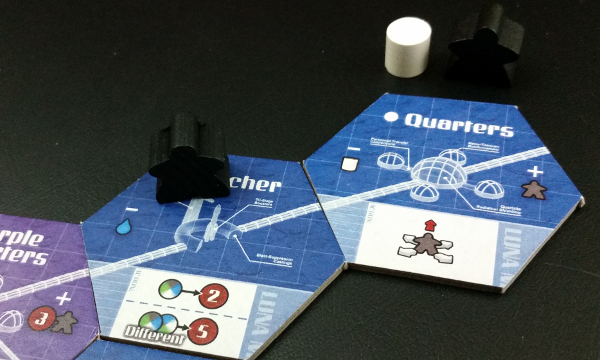

Lunarchitects begins with each player’s base consisting of their central Quarters tile. This tile contains a starting resource bonus, your initial astronaut, and a tile action when the space is activated that lets you either move your astronaut to another tile or shoots her out into space in exchange for a Rocket resource. This Quarters tile is also the nexus point for your base’s transportation system, illustrated as two intersecting pathways. This is a key component not only to how your base will be laid out but which tiles you’ll seek throughout the course of the game.

Additional tiles are gained by way of the blueprint board. Here, players take turns selecting tiles and adding it to their own blueprints. Yes, it can be a bit strange that hypothetical modules are a limited commodity during the course of a blueprint competition, but it probably has to do with budgeting or regulations or such.

In any case, the stack of ‘Initial’ tiles are randomly laid out. Players then take turns claiming precious, precious tiles. Turns in Lunarchitects aren’t in a set pattern, however. Instead, the person in the last place position on the board goes next. On your turn, you’re able to move to any tile in front of you, claim that piece and take its spot. The catch is that while you are able to take any tile on the board, the further ahead you jump of everyone, the far fewer turns you’ll get to claim other useful tiles. In turn, this means less opportunity to create resources and generate VP.

It is this constant pull of desire between trying to claim the most optimal tiles for your base and ensuring you’re able to take as many turns as possible that gives Lunarchitects much of its elegant charm. For instance, there will be times when you may have to grudgingly sacrifice a more ideal tile to another player because you don’t want to be skipped too many times in a row.

Adding a newly claimed title to your board is similarly straightforward. First, you pay its purchase cost (if any), and find a legal place where you can put it. Tiles that contain pathways must be added to one of the two existing lines, whereas those without them cannot. Additionally, you are only able to put a new tile next to an existing tile containing one of your…Meeplenauts?

We’re not sure if they’re called Meeplenauts, but we’re running with it now.

Once added to your blueprint, many tiles provide some immediate benefit, such as generating one of the game’s four major resources (Food, Water, Air, and Rock) or supplying additional Meeplenauts.

Finally, you may then activate your newly-constructed tile and any adjacent to it for their effects. Many tiles in Lunarchitects chain off of one another to create different kinds of strategic engines, and it is here where the game really showcases its own self-worth. There are multiple ways to build resources engines in the game, allowing players flexibility to decide their path. Indeed, much of the game’s appeal is trying to figure out which approach to take and how to craft the most efficient way forward over the span of an hour while competing players are attempting the same thing.

Surprisingly, most of the time this all transpires without feeling overly complicated or reductionist. There are certainly some late-game moments where you’ll have to pause and do some calculating, but generally speaking, Lunarchitects doesn’t let its depth of choice interfere with the flow of the game.

Adding the Mine tile also activates the Reactor and Distiller. The Outpost would too, if it had any effect.

Prototype Shown

There may be cases, however, when you don’t have all of the necessary resources to purchase a tile and / or take certain activations. Luckily, because capitalism exists nearly everywhere – even in theoretical moon bases – players have access to a light marketplace exchange.

At this market, players may freely trade VP in small doses for desired resources, or conversely, trade in small amounts of resources to claim VP left behind. While minor, this smooths out resource disparities and ensures that even if you don’t always get the perfect tile selections, no one can get truly stranded in space. At least, on paper.

After claiming a tile, a new tile is placed in your old location on the blueprint board. This is done continually such that the only empty tile on the board is the one right behind the person last in line. Then the new last place person (which could still be you again!) takes their turn. To ensure the game doesn’t end in boring cases of leapfrog selection, though, Lunarchitects always behaves as if there are at least four people playing at all times, which proves to be a wise design decision. In those cases, absent players are replaced by a dice-rolling neutral player instead. In Lunarchitects, that’s referred to as Spot, the blueprint-stealing dog.

There’s Spot. See Spot run? See Spot building his own Basestar blueprint? Run from Spot.

Scoring in Lunarchitects is done at four different intervals, which happens every time all players complete a full lap around the board. During scoring, players are awarded VP according to a lap-scoring tile condition randomly chosen at the beginning of the game. Each of these scoring schemes care in some fashion about the number of Crystals, Rockets, and / or Red Tiles in your possession, awarding VP accordingly. Whether it’ll be advantageous to focus on a single kind or diversify will depend on the scoring scheme.

Similarly, after the fourth lap-scoring, the game is over. Players gain additional VP from two randomly chosen endgame scoring tiles, and the person with the most VP is deemed the best person to oversee the new moon base project. Each of these three scoring tiles fundamentally alters your focus during the game due to the amount of VP they’re potentially worth, while at the same time providing a nice bit of gameplay variety and replayability each playthrough. It would be nice to proportionally more unique tiles during the later stages of the game instead of modified repeats of earlier ones, but since the game is remarkably balanced as is, you shouldn’t feel bad. Besides, if you’re constantly jettisoning Meeplenauts in a maniacal fervor for Rockets, you’re probably going to want those late game replacements anyhow.

In typical tableau style, this is done with brains over brawn. Instead of sabotaging one another for points, Lunarchitects pits players against one another in a station-building contest that revolves around skilled efficiency and timing more than direct confrontation. Essentially, what you have is four rounds of snaking blueprints from one another.

If you’ve played the game Glen More, much of this may sound eerily similar. Because, well, it is. Lunarchitects freely admits it used Glen More as its starting foundation, but this game reaches beyond the parameters of its progenitor and aims for something slightly more lofty in its execution. While Lunarchitects is clearly a spiritual successor to the classic game, with many of Lunarchitects’ mechanics being derivatives of or inspired by Glen More, to write Lunarchitects off as a mere re-skin would be a mistake. Think of Glen More more as…this game’s blueprint.

Lunarchitects is Suburbia in space, all with the tone of a Glen More brogue. And the end result is certainly praiseworthy. For starters, the game is fairly streamlined; it does not wont for depth of choice, nor does it lack the capacity for tactical maneuvering. At the same time, the game also never feels like it drags on. Quite the contrary: Lunarchitects behaves similar to Race For the Galaxy, where the game appropriately ends right as you feel like your engine is about to take off.

With a refreshingly unique theme, multiple strategic avenues to victory, and the right amount of non-combative tactical manipulation for a game of its caliber, Lunarchitects has all the right materials for success. It just may need a little boost to get it into orbit. If you think you’re up to helping build Luna City One, then you can blast right on over to its Kickstarter page and sign up!

Photo Credits: Lunarchitects cover by Iron Kitten Games; Futurama by Comedy Central.