Board games have a nearly boundless array of thematic options to choose from. They are, after all, an extension of generalized play, and play often intersects with imagination. A game can therefore take on any theme we deem worthwhile, from the most outlandish and esoteric to those grounded in everyday life. If you can imagine it, there exists the potential for a game about it.

Of course, it doesn’t take much scratching below the surface to notice that the hobby, for a variety of reasons, has specific themes that it returns to time and time (and time) again. For every game about Archibald Banderwathe flying around Proxima Centauri in his modified semitrailer*, there are 50 games about farming. Or zombies. Or Cthulhu. Or battlefield reenactments.

Or trains.

There are so many games about trains, in fact, that it has its very own subgenre: the 18XX.

18XX games are renown in the hobby for being long, complex, math-laden, and oh-so-dry, but also highly rewarding experiences if you let them. From afar, 18XXs seem prohibitively confusing, and they outwardly present a more substantial barrier to entry than nearly any other gaming subgenre around. So much so that while these games of railyards and rail barons have an ardent and active fanbase, many gamers either deliberately or instinctively choose to steer clear of them entirely due to the intimidation favor.

18XX games are renown in the hobby for being long, complex, math-laden, and oh-so-dry, but also highly rewarding experiences if you let them. From afar, 18XXs seem prohibitively confusing, and they outwardly present a more substantial barrier to entry than nearly any other gaming subgenre around. So much so that while these games of railyards and rail barons have an ardent and active fanbase, many gamers either deliberately or instinctively choose to steer clear of them entirely due to the intimidation favor.

Here’s the thing though: at their core, 18XX games are essentially just a combination of route building and economic simulation via buying and selling stocks. When you pull back the enigmatic shroud surrounding them, at the end of the day most 18XX games are just about buying trains, laying track, hoping those investments increase the company’s stock price, and then using the payouts to repeat the process over and over again. That’s it.

One largely inescapable thing with an 18XX, however, is that the overwhelming majority of them are not short games, with most easily taking three hours or more. So for many gamers wishing to try their hand at one, that sort of commitment can be prohibitive, especially if it’s just to try and see if it’s something they’ll enjoy.

This is something that was very much on the mindset of designer Raymond Chandler. A fan of both heavy Euro games and of 18XX style expeditions, Raymond recognized how much of an issue time factors into which games make it to the table – including his own – and took it upon himself to address that.

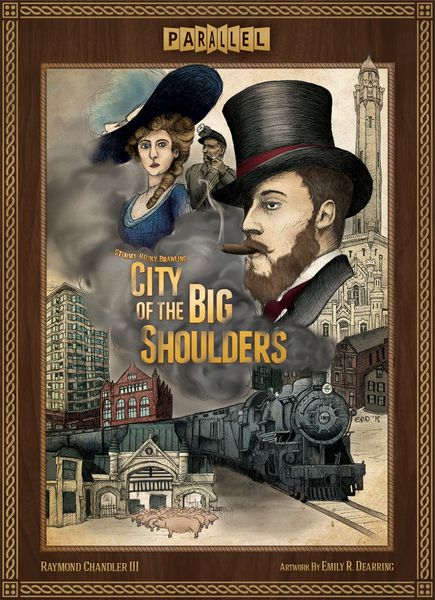

Enter City of the Big Shoulders by Parallel Games, a 2-4 player game that’s one part heavy worker placement and one part 18XX style stock manipulation that plays in 2-3 hours.

Sure, 2-3 hours is still a commitment, but it’s comparatively much more manageable than setting an entire afternoon aside just to see if these brands of trains are your thing.

Set over five rounds, each representing a decade, players are business magnates helping rebuild the city of Chicago after the great fire of 1871. Your goal, as you might expect, is to have the most money at the end of the game. Because that’s sort of what business does.

At the beginning of the game, each player starts off with a pair of Partners (worker meeples) and a bountiful $175 in their pockets. That money is quickly invested, however, as before the first round, you will be tasked with purchasing your initial company.

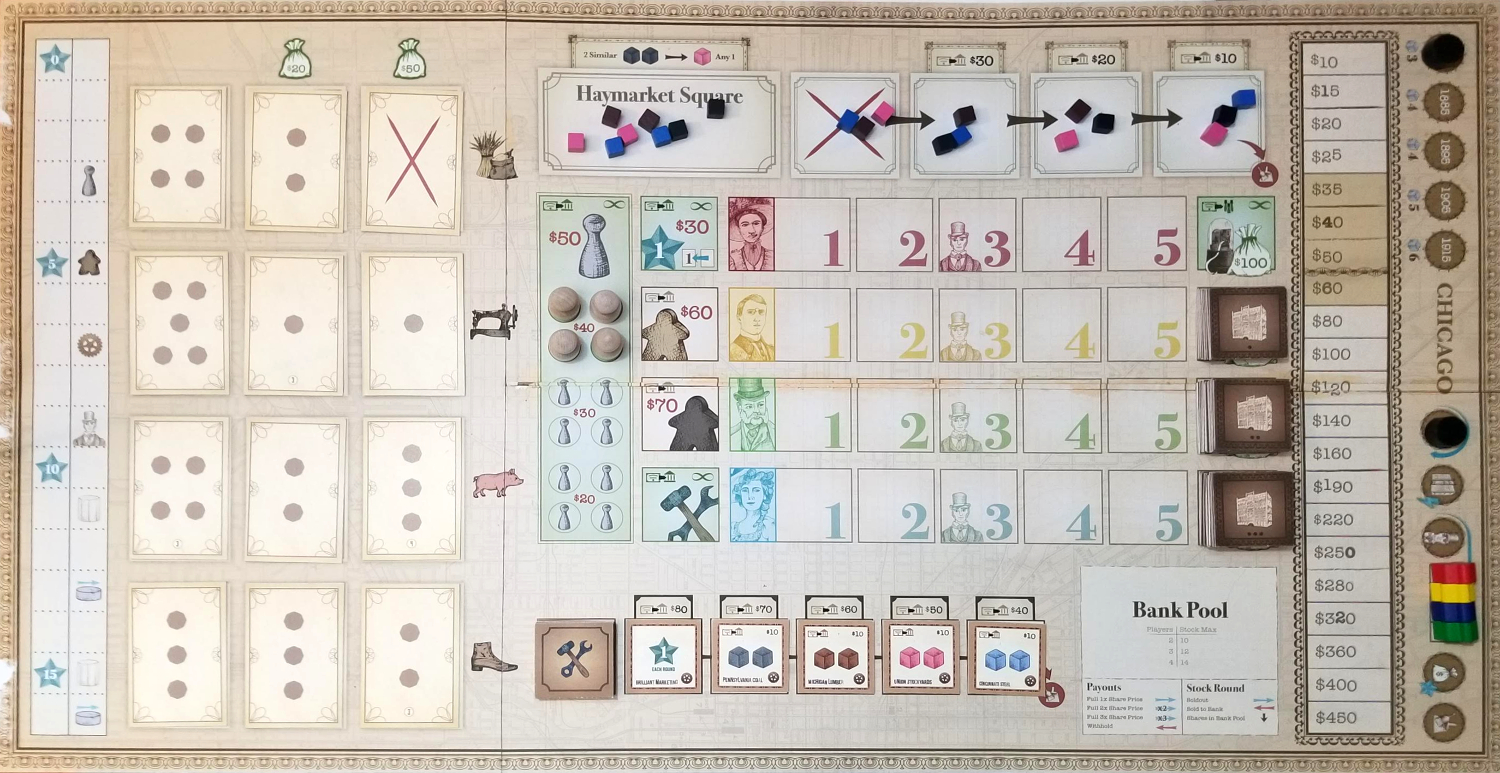

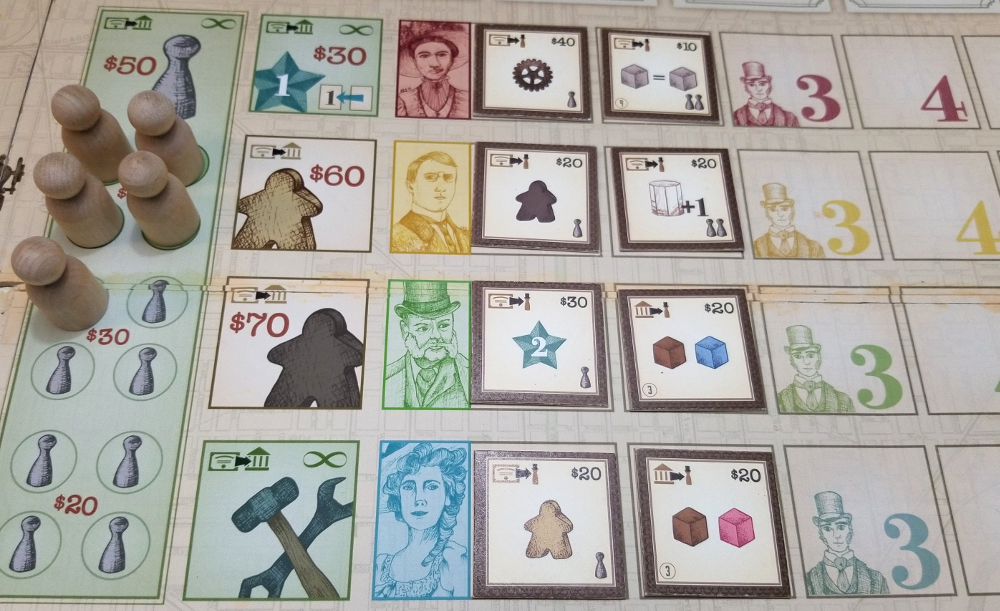

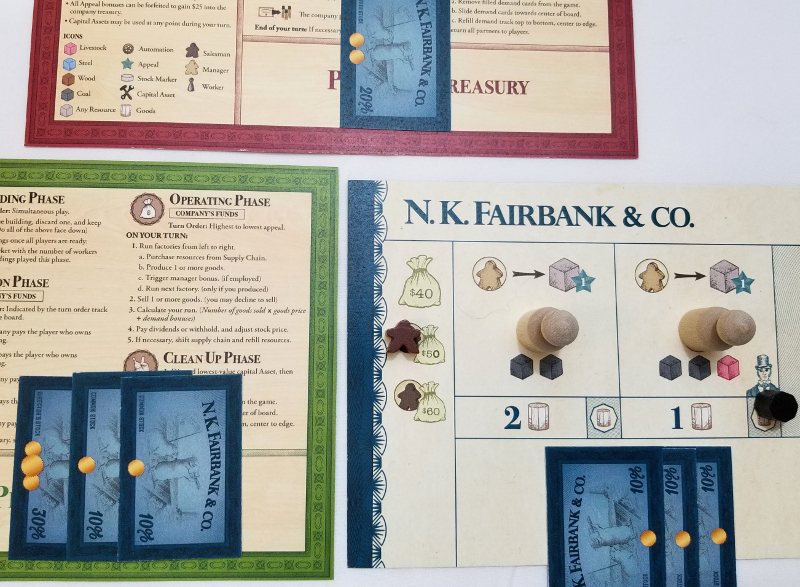

Companies in the game all work in the same manner. Each company contains 2-3 factory slots which require generic employee units and raw materials in order to produce goods to sell. Over the course of the game these companies can be upgraded to increase factory output, generate bonuses, and increase the sale value of those goods. Every company produces goods for one of four different market types, and each comes with an Appeal value of 1-3. Appeal not only provides one-time bonuses to a company as its Appeal value rises, but it also determines the order that companies operate later in the round.

Moreover, much like the oft-questioned name of the game (which is taken from a poem about the city), CoBS does an excellent job infusing some thematic business-related flavor to the game, as each available company was founded in the Chicago area during the latter half of the 19th century.

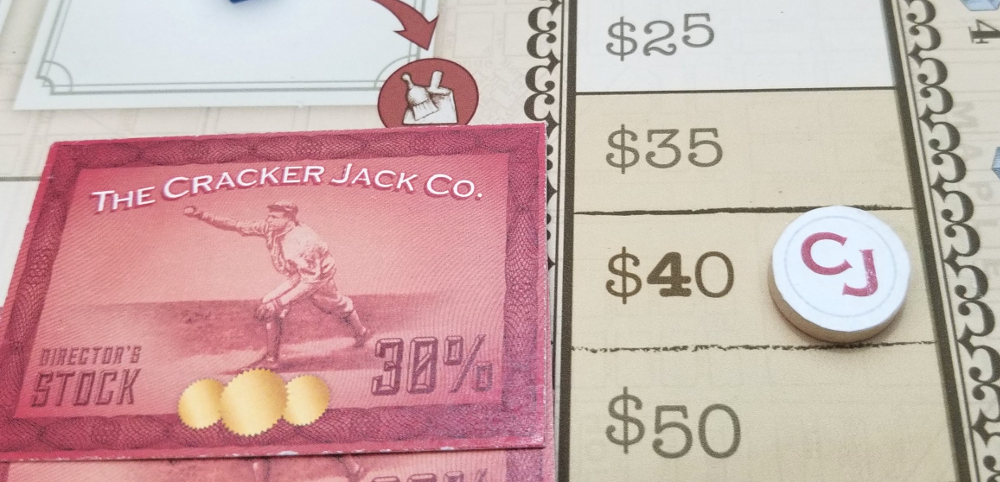

To start a company, a player simply chooses one from the available pile and must invest their personal money into the company by immediately purchasing stock shares. Every company has 10 shares, including a 30% “Director’s Share” that denotes ownership of said company. To attain this, you must decide on an initial stock price between $35 and $50 and then purchase the Director’s Share. The stock certificate is added into your personal supply, whereas the money you spend is added to the company’s treasury, along with its 7 remaining shares.

Setting the stock price of Cracker Jack at $40 will initially cost you $120 for three shares

Prototype Shown

Right out of the gate, City of the Big Shoulders introduces you to one of the two key 18XX concepts it has adopted: company investiture. That is, in this game you will be managing multiple piles of money: your personal supply of cash, and the coffers of each company you own. If you can handle this super advanced concept of having several stacks of funds, however, then you’re do just fine.

Once everyone has a company, the rebuilding can begin.

Each round in City of the Big Shoulders has four main phases, followed by a cleanup phase: Stock, Building, Action, and Operating.

During the Stock phase, each player takes turns deciding whether they want to buy and/or sell stocks. Here, you can choose to sell any stock (other than your Director’s Shares) to the bank. This provides a payout equal to its share price, but it also causes that company’s stock value to drop for each share you unload. Additionally, you also have the ability to buy one available stock. This can be one sitting in the bank, in any company’s treasury, or if you have the cash and desire, by starting additional company in the same manner as before. Buying a company’s stock adds that money to its treasury, giving it an influx of cash to be spent later in the round, true, but also allowing you to potentially profit off that company’s success as its stock price rises. In this game, the idea of spending money to make money isn’t just an aphorism: it’s essential.

This continues until everyone passes in succession.

The next two phases focus on the worker placement part of the game. During Building, each player add new worker placement spaces to those already available on the board. Every round you are dealt two Building spaces (three in the first round). These reflect minor enterprises and improvements the city is making over the course of time…with your help of course. You choose one to add to the board face down in your row, one to discard, and one to hold on to for the next round. These spaces are then revealed, becoming available worker spaces for the remainder of the game.

The result of these actions, especially when combined with the muted but satisfying color scheme of the board, provide a twofold reward. First, it ensures a fair amount of replayability as to when (or if) certain tiles will appear in each game. Second, they create a visibly appealing Industrial Era inspired mosaic of Euro gaming iconography. For a game of its weight class, most of the iconography in Big Shoulders is surprisingly easy to understand, which is incredibly beneficial towards reducing potential information overload. There is already enough to focus on in the game without trying to decipher what every little symbol means, and this game almost completely sidesteps that issue.

During the Action phase, then players take turns placing their Partner meeples, acting on behalf of any of your companies, to take various actions on the board. Most of the actions in CoBS revolve around purchasing employees or resources, or upgrading various parts of your company’s factories. This can include adding Managers, which provide bonuses when a factory is run, Salespeople, who increase your sales, Automation, which displace employees in your factory while potentially increasing your output yield, or Capital Assets. Capital Assets are tiles which provide one-time effects when purchased, but if your particular company has a slot available, they also become an action you can activate for free once per round.

Blue uses this action space, but the company must pay the Yellow player the $20 activation cost

Prototype Shown

Most of the worker placement elements in City of the Big Shoulders will feel familiar, though it does come with a pair of clever twists.

First, barring a handful of the core spaces nearly every space in the game requires paying money to use them. Sometimes this is to the bank, but often that money goes to the owner of those spaces. Second is the degree to which strategy plays into selecting which Building space to add each round. Sometimes you’ll be encouraged to put down spaces that you personally want to use to benefit your own company. This not only allows you the means of improving your own assets, but you get your company to pay you for the privilege.

Hey, nothing like lining your own pockets.

On the other hand, you could select a Building by playing into your opponent’s desire for such spaces, knowing they are going to want access to it, thereby guaranteeing an influx of cash while you pursue other actions. As the rounds progress and players gain an additional 1-3 Partners through various means, carefully balancing the tile selections between necessity and incentive is a fun and fresh way of providing variability to the worker placement portion of the game.

Further reflecting these Euro-style influences, competition in this game revolves more around jockeying for early turn order positions in each phase than overtly undermining or blocking one another. In CoBS, direct interference is purposely limited. This may be seen as a deterrent to some, but with so many moving parts, this game wisely opts to keep players focused more on maximizing their own profits without having to also worry about being unduly hindered by their opponents.

With enough employees and materials, Doggett runs its first factory, generating 2 goods. A Salesperson raises the sale value to $60 per good, and a Manager provides a reward of both a free raw material and point on the Appeal track

Prototype Shown

The last major phase is Operating, in which players purchase raw materials from the marketplace and attempt to produce goods. Factories are run sequentially from left to right generating generic good of that company’s type, which you then sell to one of three possible Demand tiles – reflecting the needs of the conspicuous consumer. (Think Arkwright). For each good delivered, your company generates that much sales revenue. Completing the first or second Demand tile also provides a sales bonus.

You must then decide what you want to do with the money, because unfortunately throwing a Gilded Age style party isn’t an option.

This is where the game demonstrates its other main 18XX influence: the stock payout. If you decide the company should keep the entirety of that revenue, all of those hard-earned greenbacks are added to the company’s coffers. However, this causes the stock’s value to drop by one. Usually, the best course is to instead “Pay Dividends”, meaning that your total paid out among the 10 stockholders. This means far less money for the company, but it could mean beaucoup bucks for you.

N.K. Fairbanks paid out $14 per share, giving $28 to the red player (2x$14), $70 to the green player (5x$14), and $42 to its own treasury (3x$14)

Prototype Shown

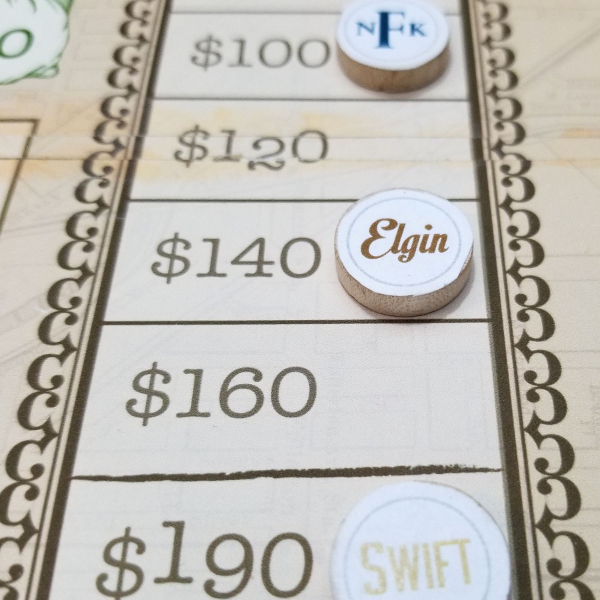

Moreover, this is also the main way that the company’s stock value rises. If the total amount you made via production is at least equal to your stock’s value, it goes up one space. If you managed to generate at least twice or three times the value, it goes up two or three spaces, respectively. Ergo, the more successful your factory output is, the higher your stock value rises, and the more you get paid – both now and at the end of the game. Not only is this process instrumental to winning, but the game also manages to impart a real sense of accomplishment in getting that stock to climb ever upwards.

It should be noted that while CoBS strives to minimize the burden of math on the player, it is inescapable with this kind of stock system. Basic addition, division, and multiplication is in abundance, both during the Operating phase and endgame calculations. Although the game ardently strives to not make it overly punishing, potential player should be aware that it makes Power Grid money management feel tame by comparison.

Once every company produces, there is a quick cleanup phase, and then the next round begins.

The Elgin company generated $290 of revenue, which is more than twice its current $140 value. Its stock price will go up two spaces.

Prototype Shown

After the fifth round, the game ends. At that point, players check to see who accomplished the game’s five endgame Goal cards for some bonus financial windfalls, each of which are randomly picked at the start of each playthrough. Then everyone’s stock holdings are cashed out based on their current value. Besides one specific Goal, money left in company treasuries provide nothing beyond the tacit acknowledgement of being a company run well.

Whoever has the most player cash on hand gets to claim the mantle of the next Chicago bigwig…just in time for the Great Depression.

Hey, no one said capitalism was kind.

So how does City of the Big Shoulders pull off the seemingly impossible and make a more accessible 18XX game?

Well…it doesn’t, honestly. But that is neither the game’s focus nor its primary intent.

Because of the inclusion of the stock market mechanics, there will be the instinct to brand CoBS akin to an ‘18XX filler’, a game for the enfranchised fans of the genre to put on the table when they don’t have time for something longer. And while there are obviously aspects that this contingent of gamerdom will undoubtedly enjoy here, there’s also a lot of room for them to be left wonting. CoBS was clearly designed to be far more forgiving and far less aggressive than a full-blown 18XX. For the ardent rail-goer, this Chicago stop may be a bit too simplified for their tastes.

Instead, this game accomplishes something even more valuable: providing a pathway for introducing 18XX concepts to gamers looking to learn about them in a very palatable way. City of the Big Shoulders is the 18XX game for non 18XX gamers. Though its visible stock market and corresponding antics are the primary vehicle of how you ultimately win, the means by which you get there in this genre-spanning hybrid is still very much rooted in its Euro side, putting it in many ways closer to titles like Madiera, Lignum, or Arkwright – a game that this one patently drew inspiration from – than to a full blown 18XX setting.

With poise and quiet self-assurance, City of the Big Shoulders has accomplished something few other games have even attempted, let alone pulled off: successfully blending Euro and 18XX style elements together in a way that’s thematic, balanced, engaging, and highly strategic. Player actions can plateau a little towards the end of the game, having multiple turn orders takes some getting used to, and there is inescapable number crunching at times to contend with, but the vast majority of the Big Shoulders experience is a pleasant blend of two disparate game styles coming together to create something representing the best each has to offer.

If you think you’d like to try hoisting this hefty hybrid game onto your own big shoulders, you can do so right now over on its Kickstarter!

This project has earned the Seal of the Republic

*To our knowledge no such game currently exists about dear Archibald, but if you decide to take up that challenge, be sure to remember us.

Photo Credits: City of the Big Shoulders cover and artwork by Parallel Games.