Keyflower envisions burgeoning villages in a new land with additional settlers coming in every few months. It’s a time of difficulty and struggle, as people balance improving their own lives with the basic necessities of survival.

In some games, this is played out in grim and trying scenarios, rife with genuine tumult and turmoil of the times.

In Keyflower, it comes across more along the lines of “Blue Meeple Four is sending his son to live in the neighboring village in exchange for a shipment of Stone”.

The Premise

It’s a hard life for the newly-arrived meeples aboard the Keyflower. Over the course of a year, players put these meeples to work acquiring resources and special skills that they will need in their villages as the year carries on. More meeples arrive each season, but as the numbers grow, so too does the competition, as only one village will be able to boast they are the best equipped by winter’s end.

The Rules

Keyflower is a tile-based Worker Placement game and Auction game in one. Setup requires a decent amount of table space for the different tile stacks, resources, and Skill tokens used. The number of tiles used in a game varies and each tile is unique, so players will need to consult the full rules for a detailed explanation on how many tiles are utilized and what each one does.

To start, each player receives a cottage-shaped player screen, a home village tile, and randomly draws eight meeple workers which are kept secret from other players. Workers come in three colors, though a fourth can be added to the pool through various actions throughout the course of the game. Additionally, each player is given 2-3 Winter tiles that are also kept secret.

Keyflower takes place over four rounds: one for each season. Spring tiles, as well as the Turn Order and fully-stocked Ship tiles are laid out in the center area to begin.

Each turn, a player may perform one of three options: Use a tile, Bid for a tile, or Pass. Using a tile means a player takes one or more workers of the same color and places them on the tile to take its action. This may be any tile, be it a center tile, the player’s own village tile, or a village tile of another player. If no workers are on or around the tile, the player may choose any color workers to use. Otherwise, the color must match those present. The number of workers placed must always be higher than the previous action on that tile, and no action may have more than six workers on it.

The first player used Blue to bid, so only Blue may be used. The current winning bid is three.

Tiles in a player’s village may also be upgraded. Upgraded tiles have more powerful abilities, and many of them score VP at the end of the game. This same action also allows the transport of resources around a player’s village for various storage and upgrading purposes.

Secondly, a player may Bid for a tile. The player chooses one more workers and places them adjacent to the tile. Bidding has the same color restriction as Using the tile, but bidding does not have a worker limit. If a player is outbid during the round, they may re-raise their bid amount or allocate those workers elsewhere. At the end of the round, the tile winner will add it to their village.

Players may also bid on Turn Order tiles, though they are not added to a player’s village until the final round. Instead, the Turn Order winners set the order in which Ships (full of precious settlers and Skill tokens) will be chosen, as well as determining the first player for the next round.

Lastly, a player may Pass. Passing a turn does not prevent a player from taking another action later on – unless all players pass in succession. When that happens, the round ends.

At the end of Spring, Summer, and Fall, village tiles (and any workers on them) are awarded to the player with the winning bid. Any workers in a player’s village or from unsuccessful bids are returned to them, as are the goods from their selected Ship. The Ships are then restocked according to the season, and any unclaimed center tiles are replaced with tiles from the next season.

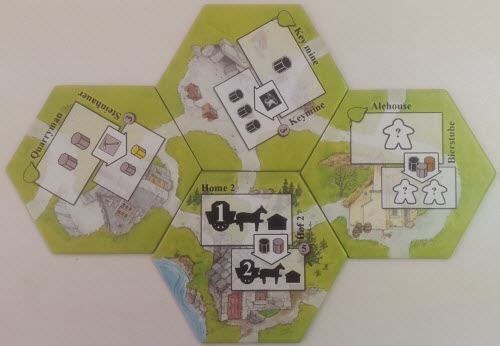

A sample village at the end of Spring, complete with a couple resource-producing tiles and a worker generator.

Winter plays similarly to the other seasons, except that players choose which Winter tiles are added to the center area. What’s more, the Turn Order tiles (and resulting Ships) are added to a player’s village at the end of Winter. At that point, the player with the highest valued village is deemed the winner, as they clearly have the most industrious community to endure tough times.

The rest may or may not survive the harsh winter conditions of the realm. Most likely…not.

Mind The Gap

Board games are, by their nature, a social enterprise. They’re a medium where people can go to socialize, to think, to stretch the imagination, and to escape from the world for a little while. Above all, though, they’re about having fun. If someone feels like they no longer have a chance at victory (or at least success) they may simply give up and stop trying. This can create lopsided games. The two most common causes for this to happen are luck and experience. Luck is one thing – if you’re rolling twos and they’re rolling sixes, it simply isn’t your night. Experience issues, on the other hand, are easier to address.

This Fall boat has a coveted Green worker, fresh from Greendonia.

Generally, because of a game’s scope or knowledge of established strategies, the more complex a game is, the more it favors the frequent player. Game design adds things such as higher luck or a co-op approach to mitigate this effect, but for Euro-styled games such as Keyflower, that doesn’t happen. Instead, these kinds of games merely advocate playing more often to discover the variety of tactics they offer.

Indeed, Keyflower has some powerful strategies and multiple courses to winning. As a hefty worker placement plus auction game, Keyflower will certainly make Tacticians quite happy. Some approaches encourage a linear resource path, for example, while others diversify.

However, Keyflower has learning curve. This game is incredibly taut, exciting, and surprisingly balanced if everyone is on equal footing, but newcomers are at a notable disadvantage against experienced players. Almost every tile is different in Keyflower, and even with most of them easily understood, knowing what they all are and which season they appear are very useful for planning ahead.

The game won’t correct this imbalance on its own. So, if one player has substantially more expertise than the rest, we suggest playing a practice season first. If that’s not feasible, at least have new players look at the back of the rule book to see the upcoming tiles – they’re all in there. Some games allow you to compensate for early game beginner mistakes. With a mere four rounds, Keyflower is not one of them. It’s not so rigid that adjustments can’t be made, but it’s incredibly difficult to swap whole strategies midgame.

The Keys to Keyflower

Worker placement games are also not usually expected to be heavily thematic, and Keyflower is no exception. Technically the seventh game set in co-designer Richard Breese’s late-medieval meeple Keyland, Keyflower shares the same traits of luck-lite, conflict-free interaction as its predecessors.

That said, the “Key” games don’t actually overlap much except in rare cases (such as the Keythedral tile). While it possesses some pleasant visual elements, like the the decent-enough artwork and detailed player screens (though we wished they were a tad bigger to avoid falling over), the flavor stays surface-level. There’s enough present to make the game look nice while playing, but don’t expect your Immersionists to be enamored with it. Like most games of its genre, Keyflower’s strengths are in its gameplay more than its theme.

Meeples & Monopolies

One such strength of Keyflower is the surprising level of player engagement. Many worker placement games don’t tend to encourage much in-game player interaction, so Keyflower stands out in that respect. You’re routinely watching other player’s actions, as they could affect you. Maybe they’re using one of your village’s actions, or perhaps they just outbid you for a tile you wanted. It also avoids certain bottleneck issues in strategy by being able to take an action multiple times or taking an action that you don’t personally control – at a cost. For a Euro game, it’s a nice change of pace.

That said, this modest uptick in interplay still makes Keyflower far too focused for Socializers. Keyflower revolves around you continually thinking about your next best move or countermove, and even with only four rounds, the game easily hovers around the stated 90-120 minute range.

The limited rounds and time frame also won’t sit well with most Strikers. Keyflower has factors that will appeal to them, such as having a clear objective, a low degree of luck, and there are ways of blocking other player’s preferred moves. However, the aforementioned difficulties with righting the ship due to early missteps coupled with the relatively slow pace of the game means Keyflower will likely not keep their rapt attention in the long run.

The same can be be said for Daredevils, who will also likely lose interest in the game after a playthrough or two. The more structured the game, the less room there is for a Daredevil’s offbeat approaches. Keyflower has multiple paths to victory, but the game doesn’t reward outlandish tactics. This isn’t a surprise, as Daredevils usually have issues with worker placement games.

Winter has come. This player needs to move precious Iron around, but others have made his efficient Wainright transport tile much more costly to use.

On the other hand, the degree of structure and planning in Keyflower will appeal to Architects. This is a game where acquiring “all the things” and building up your town is quite advantageous. In fact, two of the strongest strategies in the game – amassing as much of a specific resource or acquiring as many meeple workers as possible – both fit right into their style of play. Moreover, since meeples in Keyflower are both your workers and your bidding resources, they won’t mind parting with a few of them so long as they’re getting useful tiles for their village in return.

The Takeaway

Keyflower incorporates some enjoyable new intrigue into the worker placement arena, especially by including an auction system for collecting tiles. The dual nature of the meeples creates a fun and interesting spin on how you utilize your worker units. It forces you to weigh your decisions carefully, making difficult choices such as whether to focus on attaining goods for points or upgrading your village. Keyflower’s only stumble is that the game isn’t terribly forgiving for novice players, despite an inviting look and feel to it. This experience hurdle can be off-putting to some when trying to get the game to the table. That aside, Keyflower has an abundance of depth and strategic options without being overly complicated. The combination of mechanics meld together to create a different style of worker placement game that continues to be entertaining after many sessions. If you’re up for an innovative worker placement game, then by all means consider setting sail on the Keyflower.

Keyflower is a product of Game Salute.

Cardboard Republic Snapshot Scoring (Based on scale of 5):

Artwork: 3

Rules Clarity: 4

Replay Value: 3.5

Physical Quality: 4

Overall Score: 3.5