In Defense of Competition

Or, No, I’m Not Just Playing for Fun

Everyone take a deep breath. Inhale. Exhale. Repeat after me: Winning is fun. Winning is fun. Winning is fun.

Winning is fun, and if I didn’t think so, I would have chosen a different hobby. As gamers, we’re constantly keeping score: How many farms does she have? If I complete this road, will that let me take the lead? Do I have enough gold to get me through this next round?

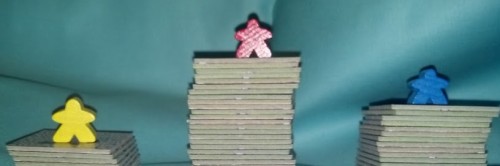

We spend our leisure time counting, and then we assign value to those numbers: first, second, third, last…

No, really, think about it for a minute.

I know that this is a simplification (some may say an over-simplification), but that’s what we do. In good games, the arbitrary accounting systems are hidden beneath layers of mechanics, plot, and theme, but they’re almost always there. And, as gamers, we love them. It’s these accounting systems that tell us whether we’ve won or lost, and it’s our knowledge of them that allows us to manipulate and strategize over the game board.

I know that this is a simplification (some may say an over-simplification), but that’s what we do. In good games, the arbitrary accounting systems are hidden beneath layers of mechanics, plot, and theme, but they’re almost always there. And, as gamers, we love them. It’s these accounting systems that tell us whether we’ve won or lost, and it’s our knowledge of them that allows us to manipulate and strategize over the game board.

I’ve yet to meet a gamer who doesn’t enjoy these systems, either implicitly or explicitly. I’ve yet to meet a gamer who wasn’t at least slightly competitive, who didn’t want to learn these systems and bend the numbers to his will. As a culture, this is who we are. If we see a system, we want to find out how it works. And, once we’ve done that, we want to make it work for us. We want to win.

Yet we’re often presented with the following duality: are you playing to win, or are you playing for fun?

Well? Which is it?

Somewhere between Senet and Settlers, these two goals became mutually exclusive and value-laden. Society implicity values the competitor, the winner, the one who goes out and tries. Yet it often explicitly values the player, the one who’s just in it for love of the game and who doesn’t care about the score. Society’s lips say “Love to play,” but its eyes say “Love to win.”

Have you ever seen a hollywood sports movie? They are classic examples of this juxtaposition. Down-and-out Team A doesn’t have the money, skills, or fan base of glamorous Team B. But Team A has spirit, courage, and heart, and they love to play the game just for the sake of it. Team B is only in it for the money and the fame – they don’t really care about the game. Who’s going to win the Big Game at the end of this movie?

Oh yeah, Team A by a landslide. Not because they practiced more, developed better strategies, or invested in new equipment. They’re going to win because, gosh darnit, they’ve got heart and they’re happy just to be playing.

But, you know what? They’re happy to be winning, too. I would like to just flat out contradict the idea that playing to win and playing for fun are mutually exclusive. My supporting evidence? Every time I’ve ever won a game. It’s fun! You get a rush and a jolt of confidence. You’ve mastered the system, the other players, and manipulated it all to your advantage – how is that not great? (Great for games. If you do this in real life, you might be a jerk, and that’s a whole other article.)

To say, implicitly or explicitly, that one path is noble and the other is selfish is false. Competition does not always bring out the worst in people. People are people: some are mean, some are nice, some are competitive, some are not. Being cutthroat in a game does not necessarily mean that you’re cutthroat in real life, or that you would want to be. While it is true that our gaming selves relate to our real world selves, one is not a direct copy of the other. That you can do something in a game that you would never do in real life is an accepted fact. In Arkham Horror, I can be a friendly hobo fighting Cthulu with only a flamethrower and an illegible tome. Translate that into real life for me.

What is less accepted is that our gaming selves are not necessarily idealized versions of our real selves. So, while I might be very competitive in a game, that doesn’t mean that I want to live that way in real life. Most gamers can separate the two. They can recognize that playing a role, whether in a traditional RPG or a modern board game, means little more than that you find that character interesting or beneficial.

This is part of what makes gaming fun – you can do things that you can’t in real life, and you can do things that you wouldn’t even want to do. Suddenly, behavior that is unacceptable in the real world is totally fine. Suddenly, I can be and do whatever I want – for a little while. Suddenly, I can try really hard to win, and it won’t be frowned upon.

![]()

Erin Ryan is a regular contributor to the site. What are your thoughts about games and competition? Feel free to share them with us over on our forums!

Photo Credits: Finish Line by RetailByRyan95.