To the Desk of Abraham Lincoln,

Your hat is mine and there’s nothing you can do it about it! Muwahaha!

-Sincerely Yours,

John Wilkes Booth

P.S. Yes, writing out ‘muwahaha’ was necessary!

The Premise

Pixel Lincoln is a board game representation of classic side-scrolling video games. In it, the nefarious John Wilkes Booth has stolen Lincoln’s iconic top hat, and it’s up to the President to get it back. It won’t be easy, as Booth has some sketchy technology and a host of minions at his command trying to stop him. The players are manifestations of Lincoln who must traverse time and space in order to reclaim what is rightfully his – and put a stop to his archenemy for good.

The Rules

Pixel Lincoln is an unconventional deckbuilding game, but it is a deckbuilder all the same, so setup is fairly simple. The game is played on a Level Board, with an upper and lower level. Separate decks are created for each level, the steps for which are explained fully in the rule book. Nevertheless, each of them contains weapons, Enemies, and an occasional Special Item or Character. At the start of the game, there will be five slots filled on each level with cards from the Level Deck.

Each player receives a Player Tableau, as well as a starting deck of five Jump cards and five Beardarang cards. Players also each receive a numbered Player card and two Life Cards. The person with the most change in their pocket is Player 1, and the rest are distributed clockwise. Lastly, players in turn order select which level they wish to start on and draw a hand of five cards.

Like many deckbuilding games, turns are very concise in Pixel Lincoln, consisting of only three steps. First is the Ambush step. If a player begins their turn with an Enemy in front of them, they must either play cards from their hand to defeat it, or jump over it. Should a player be unable to, they lose a Life, and they skip to the third step of their turn.

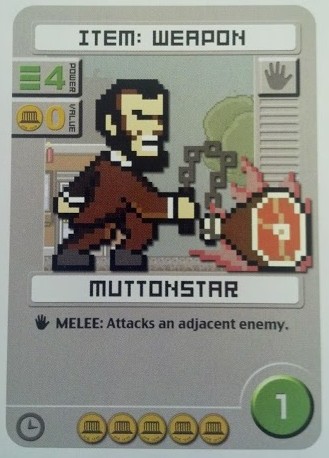

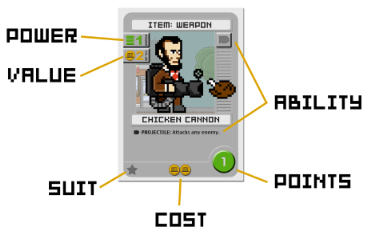

The second step is Explore. Here, players can purchase items in front of them by playing cards of a total Value amount equal to the amount on the card. They may also fight Enemies they encounter as they move.

Players defeat Enemies by Equipping items to match the Enemy’s Power Level. Doing so places that Enemy in that player’s Score Pile. (Many items also have effects that happen when used, and Enemies often have effects when defeated.) Alternatively, jumping over an Enemy or item is done using a jump card.

Players defeat Enemies by Equipping items to match the Enemy’s Power Level. Doing so places that Enemy in that player’s Score Pile. (Many items also have effects that happen when used, and Enemies often have effects when defeated.) Alternatively, jumping over an Enemy or item is done using a jump card.

When a player on a level reaches the Level deck, that level “scrolls”. Any cards behind all of the players are removed, and everything is shifted until the player furthest behind in the level is at the starting point. New cards are revealed from the deck and placed in empty spots.

Players continue to Explore until they choose to stop and proceed into the third step. In the Draw/Discard step, players discard any cards used that turn to fight or purchase items, as well as any number of cards from their hand, and then draw back up to five.

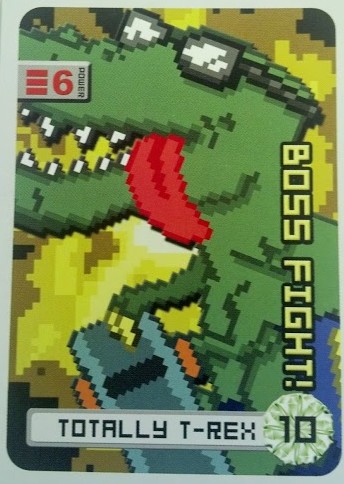

The game continues until certain Checkpoint cards are reached. When that happens, players on that level either draw a card, cull a card from their hand into their Score Pile, or switch levels. The second Checkpoint of a level becomes be the Mini-Boss, and the third Checkpoint becomes the level’s Boss. When the Boss of a level is defeated, that level is cleared. When both Bosses are defeated, the game ends.

When the game is over, players count up the total value of their deck. All cards besides the starting cards provide point values, including unspent Life Cards. Character cards provide bonuses if a player can match all of that Character’s symbols with cards in their deck. The player with the most points is determined to clearly be the real Lincoln. The rest must be mere clones. Or something.

A Genuine Dr. Wily

Perception, as they say, is reality. From society at large, gamers of all stripes endure misconceptions and stereotypes. In the US at least, adults playing video games – unless they’re sports related or are on a phone – have to contend with people believing they’re antisocial shut-ins who’d be better off doing other social activities. Likewise, whenever an adult wants to pull out a board game, the belief is that those games are all somehow just like Monopoly, and why would anyone want to willingly spend their time playing a kid’s game? Whether it’s Carcassonne or Call of Duty, both digital and analog gamers have to put up with these preconceptions. While it is changing – more slowly for tabletops than video games – we are making progress.

Yet it doesn’t help when you get gamer-on-game strife as to whether one format is superior to the other. It’s akin to people favoring regional sports teams, and it can range from dismissive to vitriolic. One way to address that is a healthy dialogue among gamers, acknowledging that each largely serve different purposes, and one doesn’t have to adhere to belonging solely to one camp or the other.

Another way is to combine the two. Enter Pixel Lincoln.

Created by Jason Tagmire due to his of childhood love of all games, Pixel Lincoln is a board game of traditional side-scrolling video games like Super Mario Bros., Castlevania, and Sonic. This is reflected in quite a few aspects of the game, though none more so than in the game’s presentation. For starters, all of the art is in 8-bit graphics. It won’t win any awards with them, but it’s visually appealing and sells the theme far better than any other facet.

The game’s theme is backed up in the mechanics too. The most poignant of these is the Level Board itself. The side-scrolling nature is pretty unique for one. Also, you frequently gain items and jump over baddies. (Feel free to make sound effects when you do.) Just like in Mega Man or Contra, you keep adventuring towards the right of the board, and you will get shifted, just as your character would have done when it changed screens on the TV.

That Pixel Lincoln also contains a surface level and a subterranean level is also a nice nod to these video games of old. You can have players in tandem with one another or going solo in each play through, adding depth to the multiplayer aspects as well.

That said, the multiple levels in Pixel Lincoln is also a double-edged sword. Both levels in the game require its own deck, and these need to be built in a specific way, with no less than five steps that include shuffling and dealing at least twice. For each deck. That is after selecting the difficulty rating you want your game to be, which stipulates which item and Enemy ranks to use. Deck creation is easily the most tedious part of the game, and while it doesn’t detract from actually playing, it feels more complicated of a process than what you’d expect from the game’s lighthearted and comedic nature. It does include a Level Builder sheet that mitigates some of this issue, but we also recommend either sticking with level decks that are set to go ahead of time and altering a card type every couple playthroughs. Additionally, if you only have two players and want a shorter game, try opting to only use one level.

Bits of The Minus World

Level deck creation aside, Pixel Lincoln is actually an aesthetically amusing game. It never takes itself too seriously – which is evident with such things as a multitude of meat-related weaponry. At times it even turns that irreverence in on itself. All of this makes Pixel Lincoln an easy game to learn, and it’s accessible beyond the ideal audiences of teens and gamers nostalgic for games of their younger years.

One group that should be try it are the Socializers – as long as they don’t have to be the one setting it up. Pixel Lincoln is straightforward goofy fun, with mild downtime; it’s not overburdened with too many tactical choices or a lengthy time commitment. Whether they opt for future sessions will vary on their sense of humor, but Pixel Lincoln in their wheelhouse.

One group that should be try it are the Socializers – as long as they don’t have to be the one setting it up. Pixel Lincoln is straightforward goofy fun, with mild downtime; it’s not overburdened with too many tactical choices or a lengthy time commitment. Whether they opt for future sessions will vary on their sense of humor, but Pixel Lincoln in their wheelhouse.

Still, this ease of access doesn’t mean it’s for everyone. Architects, for example, are likely going to want to skip this game. This is a bit of surprise considering this archetype tends to like deckbuilding games, but the difference is in the collection manner. Most deckbuilders get cards in a proactive manner: you take the cards you want for your deck, and you get to play those cards largely on your terms. Other players may interfere to some degree, but you’re still playing the deck the way you wish. Pixel Lincoln is more of a “reactive deckbuilder”. That is, there aren’t stacks of cards to choose from, and how your deck is crafted is by spending time and resources to get the item in front of you, or to skip it and move to the next item. The player here has far less control over what is available for their deck, and constantly having to scramble is not something Architects prefer to do.

Strikers will have similar reservations. Pixel Lincoln is an entertaining video game homage, but while it has Enemies to slay and Bosses to best, Strikers will have issues with the tempo. Even with all the monster slaying, it still moves with the speed of a deckbuilder. Pair that with the unpredictability of cards revealed, and you have a mix of a wacky and chaotic environment that they can’t tamper down. It’s better that they opt for the source material instead. Daredevils, on the other hand, should get a kick out of picking up bizarrely efficient weapons and running with them.

Immersionists will appreciate the oddly crafted world of Pixel Lincoln. They’ll likely enjoy the theme of a classic video game ported into board game form. Also, who wouldn’t want to stop an evil John Wilkes Booth and his army of luchador henchmen?

For Tacticians, it’s a bit of a mixed bag. Similarly to Strikers, some may have issue with the game’s chaotic nature for a deckbuilder – it’s particularly difficult to plan for the long game in Pixel Lincoln. That said, there’s certainly potential for them to enjoy it. Consistently having to reassess your situation each round makes thinking a turn ahead particularly useful if you’re able to adapt to changes easily enough. Adding in the special abilities of cards Equipped or discarded bolsters the number of strategic options available to a level they can work with. For those who can keep their plans flexible, bending without breaking, they’ll have fun. It may not have long-term lasting appeal to them, however, unless they are also fans of the theme.

The Takeaway

Pixel Lincoln bridges the divide between analog and digital gaming, reminding us that at the end of the day, what makes a good game isn’t the platform it’s on, but rather, if it’s entertaining. The appreciation of early console games has endured not because of the technology, but because so many were engaging, memorable, challenging, and above all, were able to resonate with us as young impressionable fans. In many ways, Pixel Lincoln captures that feeling as a cardboard shapshot of such games. The flavor is the most evocative part, and it does this particularly well. (You will, however, have to supply your own theme music.) A couple of the rules could use some tightening up or expanding upon, such as the ability to cull cards and the scaling issue of bosses, but that doesn’t detract too much from what is being offered. There’s a lot of variety and room for customization, helping to avoid it becoming stale. Pixel Lincoln can be played as a family game or as a game among those who will appreciate the 8-bit setting. Just watch out for the laser sharks.

Cardboard Republic Snapshot Scoring (Based on scale of 5):

Artwork: 3.5

Rules Clarity: 4

Replay Value: 3

Physical Quality: 3.5

Overall Score: 3

Photo Credits: Pixel Lincoln punching by Island Officials; TMNT by Hardcore Gaming 101.