Role Selection is an interview series in which we chat up folks who work, live, and play board games in a variety of ways to learn about the roles in the hobby they’ve chosen.

Character Name: Kathleen Mercury

Character Name: Kathleen MercuryRole: Teacher of Game Design

Location: Ladue Middle School, St. Louis

Favorite Early Game: Clue

Current Favorites: Carcassonne: Star Wars, Deep Sea Adventure, Empire Builder Crayon Rail games

Quote: “I always want (my students) to be creators. I don’t want them to just be consumers.”

Character Bio: Teacher Kathleen Mercury was at a conference for gifted students – her area of expertise – when she first heard about Stratego.

Now, she knew Stratego. Mercury has three sisters close in age, and they grew up playing a lot of games (Clue was a particular favorite). But when somebody told her it was a great game to use with gifted students, Mercury decided to do some investigating.

Stratego research led her to the broader world of hobby board games. On Craigslist, she found a copy of Reiner Knizia’s classic design, Samurai. The woman who sold her the game told Mercury about a local board game club where, during Mercury’s first night in attendance, she played Cash ‘N Guns and Pandemic.

“I was just in from the start,” Mercury said.

Mercury’s role as a teacher of gifted children allows her a lot of flexibility in determining her curriculum, so she decided to create a class on board game design.

It took a while to get things rolling. When she started about 10 years ago, “There was nothing out there for teachers who wanted to teach game design.” As she gathered resources, Mercury began to collect what she’d found at her website to help jump-start other teachers who also wanted to teach game design to their kids.

She says her teaching methods have evolved over the years, and one of the important breakthroughs came when she attended a seminar that taught the Stanford Design School method of design and prototype development. There were lessons about empathy, keeping the players in mind when designing, and daring to fail.

The Interview:

Kathleen Mercury: The more I do this, the more it goes from game design to just teaching design thinking and coaching them through this process.

Most kids in school have right-answer, wrong-answer. That’s pretty much what they know…[Game design] can be incredibly stressful for kids…So a lot of what I do is coach them through authentic failure, prepping them to be ready for their game not to work.

I don’t have kids sit and think, and think, and think, and brainstorm and write things out for the games. I get them to actually make the games pretty quickly. We prototype toward a solution, making something happen right away.

These are the things I want them to learn how to do, so when they undertake more complex problems later in life, they’re used to working through this.

A lot of my students don’t really experience academic failure up until this. This is authentic failure, where they disappoint themselves and I have to coach them through it – or I disappoint them by making them do this in the first place!

(laughter)

Matt Golec: What are some of the other things that kids get out of game design that might be seen through a more traditional school lens? What academic skills are they getting from game design?

KM: We do a lot of technical writing. They read a lot of rulebooks and write their game manuals. This is an engineering process. It’s very much at home in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math kind of classes.

Within Common Core, there’s a push toward technical writing and informative writing, and that’s one of the things I think is super important from an academic standpoint. It doesn’t matter how cool your idea is – if you can’t explain it to people so they can do it when you’re not there, it’s like it doesn’t exist.

This is where the empathy piece really comes in. How would somebody else interpret this? What does somebody else need in order to really understand your game? And that is a long process.

MG: What does a typical day look like in a game design class?

KM: We’ve just spent about a month playing a lot of games. Today we covered a lot of mechanics because we’re starting to get into the actual design side.

I have a copy of the card game Unpub, and so we’re going to use that tomorrow to practice making up games, talking about games, and talk about how they would use these various mechanics. Because they have to learn a good 20 or so mechanics in order to give them a skill set in which to work with.

You could obviously do with a lot less, and that’s what I usually recommend for teachers doing it the first time. Just give them a few basic mechanics to use: action selection, programmed action, simultaneous action selection. Those are the ones that are easiest for kids to understand how to give players choices, especially since I do not let them use dice.

I do not let them use Roll and Move. I do not.

We’ll brainstorm mechanics, we’ll talk about theme a bit, but they’re going to start having prototypes hit the table hopefully (within a couple weeks). We’re trying to get ideas on the table really, really quickly.

I’m looking for growth. I’m looking for going beyond the basic idea and really getting them to explain the choices they made.

When I used to let the kids spend a lot of time making prototypes, they were so precious. They never wanted to get rid of anything, even if they didn’t work. So by keeping them ugly, fast and cheap hitting the table, we get them playtested faster and start making changes. It’s a far, far better way to do it.

Every kid designs their own game…though they collaborate so much with each other. They probably playtest every game in the class.

There are a few things they can’t have: no sports themes, no war themes, no person-to-person violence, just because they’re the most easy, basic forms of conflict in games and I want them to be more creative than that. Also, I work in a school setting; I don’t want games where ‘I shoot you, you shoot me back.’

I have a giant closet full of clutter. Funagain Games is super great. At BGG Con, they always give me tons of leftover material and resources, and we use so much of that. I buy a lot of math manipulative and cubes. Any kind of thing I can buy that is inexpensive, comes in large quantities, is durable and cheap – that’s for board games.

Inspiration Comes At Any Age

MG: When you start the class, are there common misconceptions kids have about how you make games? Is there an ‘ah-ha’ moment, or is a more gradual learning slope?

KM: I would definitely say it’s a more gradual slope. It’s funny – they’ll come in during the second week and say, ‘When are we going to start making our game?’ And then, two weeks into game design, they’ll say, ‘When are we going to start playing other people’s games?’.

MG: (laughter) That’s neat.

KM: That’s the thing, because it gets harder with every step. Coming up with the theme, theme is hard. Then when you’re trying to fit your mechanics onto that – what am I going to do, what am I going to choose? And prototyping is hard, and playtesting – figuring out where the problem is and identifying it, then making a new prototype, etc.

The more ambitions they want to be in their games, they harder they are going to be to design. For me, it’s a balance between helping them make the game they want versus trying to help them make something that’s more appropriate for them.

I’ve been surprised on both ends. I’ve had kids who I thought were capable of so much really, really struggle, and I’ve had kids who I was surprised by how much they were able to create.

MG: Can you tell me about some memorable games you’ve had over the years?

KM: One of them almost got published, but the company that picked it up was sold, and then sold again, and it just got lost in the shuffle.

MG: That’s a shame.

KM: That one was really good…I’m hoping that I can get (the student) in front of some different publishers so they can take a look at it. It’s called Infection. It’s a two-player game where one person plays the virus, and the other person plays the body. The virus is trying to take over the body, and the body is trying to defend itself against the virus. So there’s no hidden information, it’s all right there on the board, so it’s all just pure decisions and strategy.

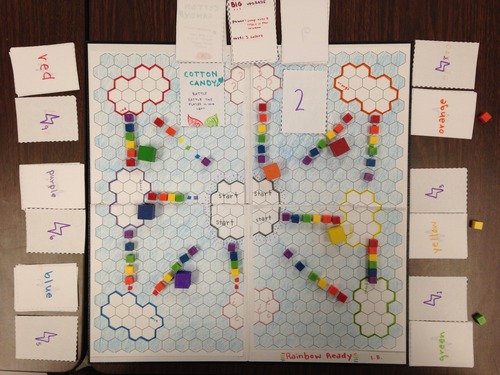

Rainbow Ready is another one that I love. This one was designed by a girl. Players are unicorns trying to hop from cloud to cloud, and to do so they need to build rainbows. The cards that you play are cotton candy cards.

One of the things that really stands out for me as a gamer and a woman, and a game designer and a woman…is access for girls. I’m making sure that we get more women into the industry, that we get more women into the hobby…just by getting girls to play games and to design games.

So the reason I love the unicorn game is because everything in it is sweet and cute and fun, and, I hate to say ‘girly’ – but it kind of is. I like that gaming, game design, is so robust that…kids can really express themselves. Whatever form that may take.

![]()

Mercury’s excitement about her student’s games comes through loud and clear, and she’s posted many more cool prototypes than we have space to print here. Luckily you can see them in detail over on BoardGameGeek.

In addition to Mercury’s website, you can most readily find her on Twitter.

Matt Golec is game designer with a background in print journalism. Combining these skills, he aims to explore and give voice to the many different jobs within the hobby industry that don’t frequently get reported on. He can be best reached via Twitter.

You can discuss this article and more on our social media!

Photo Credits: Multiple Photos from BoardGameGeek, Game Crafter, and NBC.