Fantastic Factories is the sort of game that takes a number of fairly familiar concepts and compiles them together in such a way that provides a wholly unique experience of its own. Within the game’s core mechanisms resides a number of aspects seen in many beloved games, and their appearance in this one is no accident.

To learn more about the origins and genesis of how this game went from appreciation over disparate mechanics into a game of its own, we turned to one of the co-designers themselves, who walks us through the very first stages of how we went from just okay to fantastic.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally posted by Joseph at Medium.com on November 18th to coincide with the fourth anniversary of the game’s initial design. It has been compiled together and reposted with minor edits.

Fantastic Factories has now been fulfilled to backers, and players around the world have been enjoying it! We are celebrating our 4th year anniversary of when Fantastic Factories was first conceived back in November 18th, 2015, and I thought it might be of interest to people to write about how Fantastic Factories got its start and the various design challenges that we faced in a series of blog posts. For this post, we rewind the clock back to the very beginning and share how this scrappy group of friends got together with an idea for a board game.

November 18th, 2015

As anyone in the Pacific Northwest knows, it gets really dark really early during the winter months, making it more challenging to go outside and play soccer or tennis. My good friend Allan was looking for something creative we could do inside, and the four of us (Allan, Justin, Javier, and I) decided we would try designing a board game. We pulled together some rough ideas from games we’ve been playing and talked about the parts we liked and didn’t like about those games.

In the end we decided on a few key points. We liked the puzzley dice manipulation and dice placement from Alien Frontiers but disliked the long turns. We liked the simultaneous turns of 7 Wonders and how well it scaled with players. We also liked the engine building from Race for the Galaxy but disliked the complex symbology and steep learning curve that can arise. After that meeting, we were tasked with each coming up with a prototype to bring to the following week’s meeting.

Paper & Scribbles

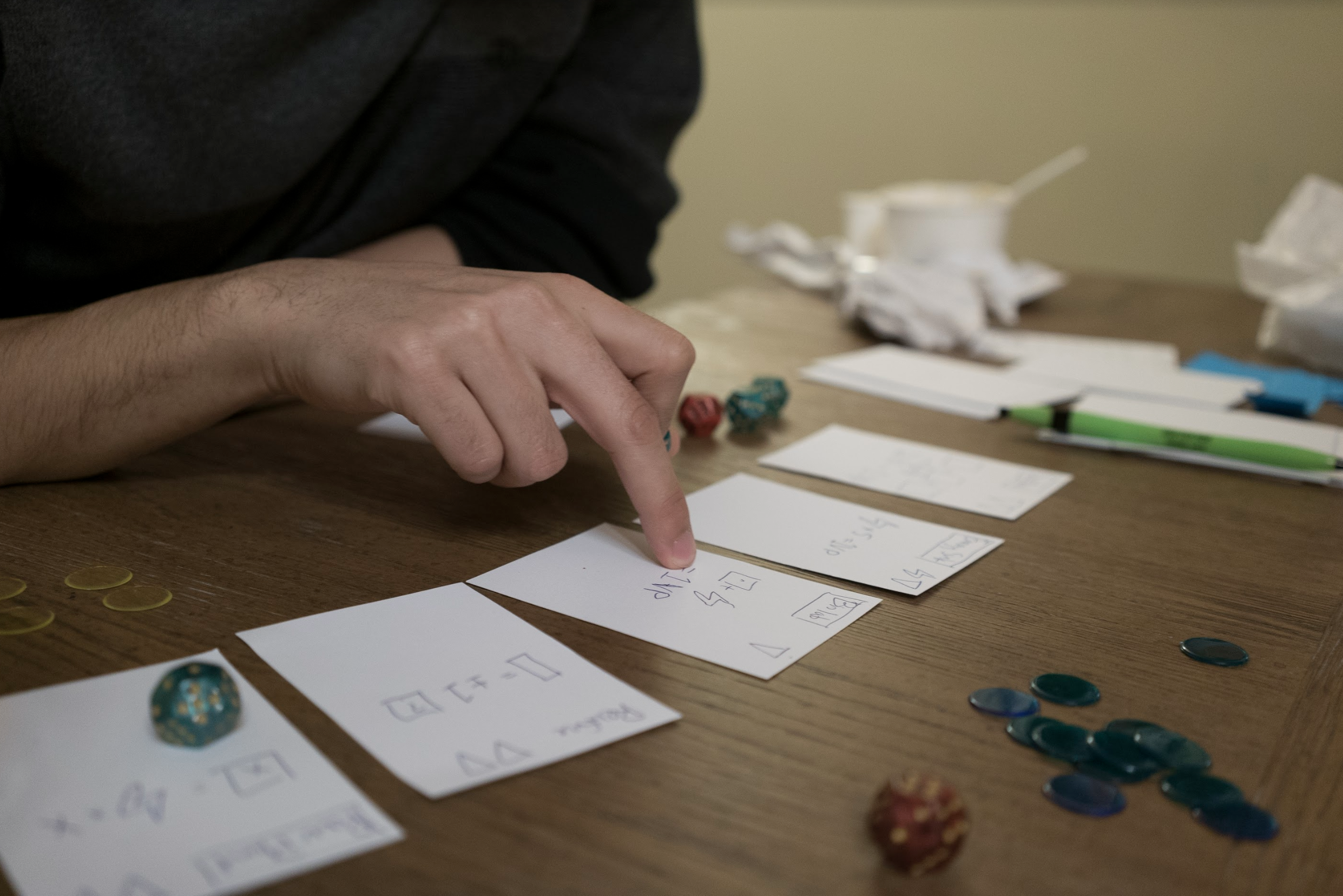

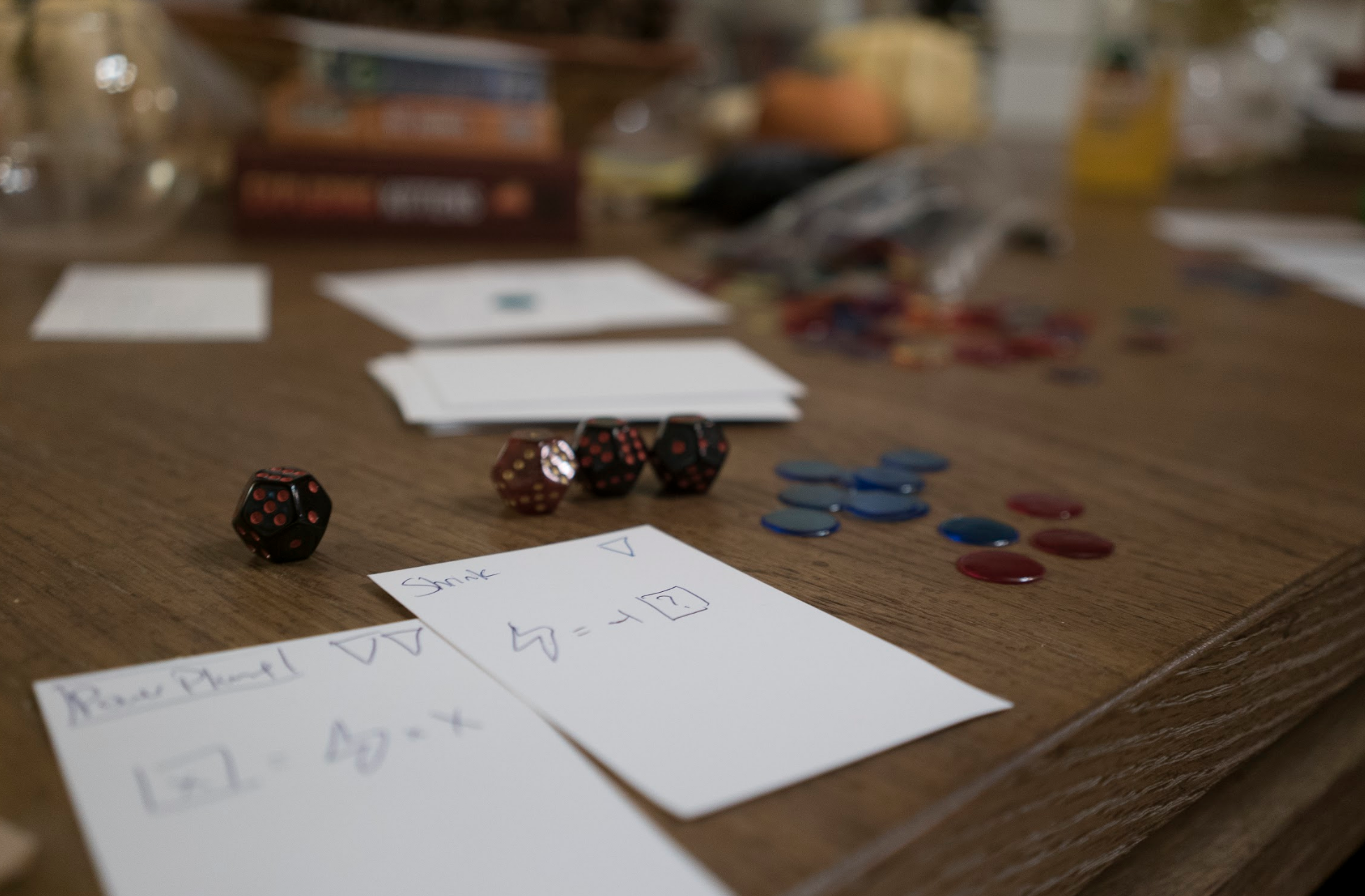

What we came up with was… rough. It was imbalanced, messy, all over the place, and the cards weren’t even cut straight. My prototype was the closest to being balanced enough to be playable, and it (kind of) worked!

I take a very mechanics-first approach to my initial game designs. The cards were completely themeless. What are now known as the Metal resources were called Gems (I can’t remember why) and were represented by an upside-down triangle. But the core idea was there: tableau building of classic engine builders and the dice placement and manipulation that came from that tableau.

The Resource System

One of the earliest design decisions that was made was to have only two different resource types. Our guiding North Star was to make our game as simple and approachable as possible (i.e. don’t design a complex system when a simpler one will do). The idea was to have as few resource types as possible while still being able to create an interesting resource system. I figured if Starcraft could get away with just minerals and Vespene gas, I could also make a two-resource system that would work. The key was to make each resource type have a distinct feel to it. To that end, two of the ground rules became that all cards would at least cost Metal to build, and all dice manipulation would only cost Energy to activate.

Number of Dice Workers

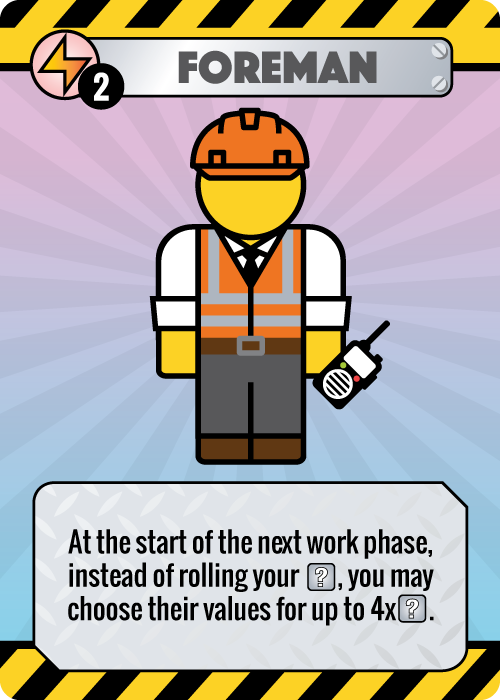

Another one of the earlier decisions made was how many dice each player would be able to have. In many worker placement games, there’s often a way to obtain additional workers, and it’s almost always the correct move to do so as early as possible. In some cases, the real game didn’t really begin until you achieved a critical mass of workers. And depending on the random outcome of your early rolls, you may reach that point earlier or later than other players.

I didn’t like the fact that our game didn’t really start right away, and I also didn’t like how, due to chance, you may be starting the game effectively a turn behind other players. So some of the ground rules for Fantastic Factories emerged early in design. These included that you would immediately start with sufficient dice to operate an engine, you would not need to gain extra dice in order to win, and any dice you gained throughout the game would be temporary. We held to these rules throughout the whole development process, and for those of you who have played the game already know that you can really hit the ground running turn 1 – even building a factory and using it on the very same turn.

We settled on 4 as the number of starting dice in the end because 3 felt too limiting and 5 allowed you to activate almost any factory far too easily, losing the tension in being able to get the numbers you needed.

More to Come!

Hopefully you’ve enjoyed reading a little bit of the design decisions behind Fantastic Factories. In the two and a half years of development there have certainly been a lot of challenges and tough decisions. Stay tuned to future design journal segments over on my Medium account, and if there is any particular part of the design you’d like to read about specifically please reach out and let me know!

Fantastic Factories’ co-designer Joseph Chen was gracious enough to supply this design journal. He can be found most readily via Twitter.

Discuss this, and other articles, on our social media!

Photo Credits: All images by Joseph Chen and Deep Water Games.