As board gaming continues to grow in popularity, it is reaching whole new swaths of potential gamers. With that comes not only whole new ideas about the games themselves but also new perspectives on matters of theme, culture, representation, and inclusivity. While this undoubtedly has and does lead to clashes of opinion as the landscape of board gaming slowly incorporates more diverse voices into the fold, there still exists the belief that the community overall will be better and stronger for it in the long run. That is, if we let it. If gaming is for everyone, then, as this series advocates, we must be willing to pursue that goal by collectively going All In.

![]()

In my debut article, I opined a bit about how communities form naturally with people around us with similar identities. That process is similar in gaming communities pertaining to our gaming identity. We tend to build relationships with people who are like us – people who share similar experiences, people who look like us, and of course, the people who like the same hobbies as us. On an even more micro level, I shared how I, like many, personally gravitate towards people within board gaming because of their play style or the types of games they prefer. Which is reassuring yes, but it also limits the potential for greater community interaction.

If I want to break out of this cycle, I need to willingly and intentionally choose to play with people who enjoy different styles of games. Personally I find this quite hard because doing so is new, out of my comfort zone, and I have no idea of my experience playing that game will be any fun.

But let’s go even deeper into our ingrained propensity to gravitate to those who are most like us. Within the comparatively small community of board gamers, we tend to associate best with those who may already share similar gaming tastes or play styles with. From there we create even smaller micro-communities of people with similar life experiences as ourselves. As a result, a game group could end up looking very homogeneous in terms of its identity.

Think of it like museum art. Everyone is there to enjoy art, but some prefer to only go look at the Dutch Masters. And some of those only specifically for Rembrandt. And some of those only for his artwork featuring men on horses…

These homogeneous groups aren’t necessarily bad, but it does uphold various stereotypes and biases of what a gamer looks like and what experiences they possess. All types of people from all manner of experiences love board games, and as board gaming becomes more larger and more diverse, to truly make it thrive we need to open up our established communities. If we want a more holistic gaming community, we must active seek to occasionally interact with those other gamers.

Personally, I do not think this will happen naturally. We must instead focus on intentional community building. But what does intentional community building look like?

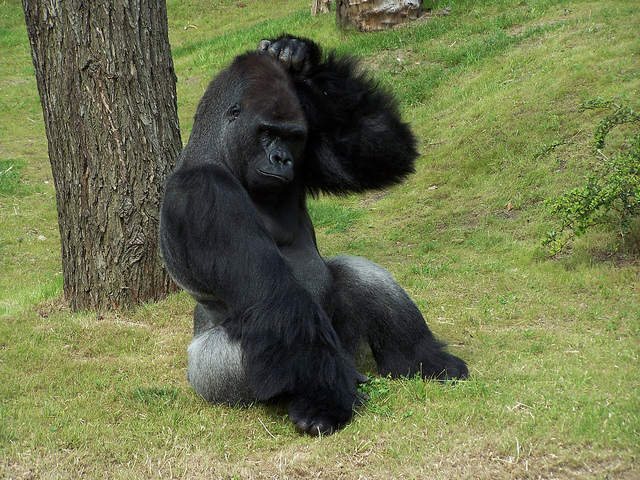

Focusing so much on our own group can be great but may also cause you to not see The Invisible Gorilla

Structure is key. Without structure, we fall back into our routines, which are informed by our life experiences and the implicit biases that comes with it. Structures may seem awkward and rigid, especially when it comes to relationship building, but it works.

Most folks I’ve spoken with on such matters like the idea of relationships and communities forming ‘organically’. Yet all organically means is that we’ll most likely fall into our biases that align with our experiences, because that is what is easy. Organic signals we should let what is ‘natural’ happen.

In gaming terms, organic community building essentially says that you forming bonds with other gamers will just happen through the normal experiences of exploring the hobby. Yet with all things being equal, using an organic approach – one without any external structures – effectively admits that the most likely outcome is that you’ll be drawn to the gamers who are most similarly-minded to yourself anyway.

From empirical experience, however, strong relationships across different groups rarely just happen on their own, and if they do, they are the exception, not the rule.

So, if the standard organic approach isn’t ideal, what would a structure look like that would promote intentional community development? Here are three example approaches.

Option One: Structured Dialogue

There are many models that exist (and backed by research) that promote healthy dialogue across different experiences. This might be the most regulated (in terms of structure) because of the need for a trained facilitator. The role of the facilitator is to keep the group on track, aligned with the goals of the dialogue, as well address and explore the intragroup dynamics they observe. This could involve interrupting participants to remind them of the community guidelines the group agreed to at the beginning of dialogue. This could be observing and calling out instances of individual or group harm to increase awareness of microagressions and repair damage caused by them.

There are different stages in models of dialogue, and each focus on different goals, such as getting to know each other by sharing experiences, increasing awareness and knowledge of experiences different from our own, bridging differences by finding commonalities, and talking through ‘hot’ topics. These methods also address the type, focus, and topic that could be selected intentionally for the group the facilitator is working with.

One of the best part of this model is the facilitator only needs training in facilitation skills – they do not necessarily need to be experts in the subject or topic. With a basic understanding of the topic and a commitment to the goal of the dialogue, a facilitator can lead a group to better understanding of each other and support participants as they explore their genuine curiosity of learning about one another .

Option Two: Pair & Share

Pairing up and sharing around a question or topic is another way to start opening people up to each other. Unlike the structured dialogue model, finding a partner and sharing with them is much less structured. There are definitely positive and negative attributes with less structure, though. First, pair and share feels less rigid and regulated, which can make it more accessible. Second, it allows two people to focus on each other, rather than a group, thereby creating an environment where the pair can really get to know each other in depth.

On the other hand, in a less regulated environment, if two people are on unequal standing without a facilitator present to address the inequity, it is possible for one participant to cause harm to the other. With a third-party involved, however, that person can prompt the participants using a series of questions that moves the pairs from low risk questions to deeper ones.

Option Three: Story Sharing

If you have listed or been to The Moth, that is what I am talking about, but to a lesser extent in terms of fanfare. This approach is a structured event where anyone in attendance can share a story within a certain timeframe about their experience, though participation from attendees is not mandatory. (I, for instance, am not a great storyteller and often think I do not have compelling life stories to tell.) While still technically a structured approach, it’s also part event, whereby the stories themselves are in the hands of the storyteller. This gives participants agency about what they want to share to the larger community.

Storytelling events usually also come alongside storytelling workshops, which can be useful in and of themselves. Through the workshop model, participants can practice writing their stories, get feedback to help shape their writing into a more cohesive story to tell at the event, and process the experience with other writers/storytellers. Storytelling can challenge the dominant narratives and implicit iases we have about other people. Storytelling can also build empathy and understanding for others. While this is definitely not in everyone’s comfort zone, stories are powerful and we should not overlook it as a way of learning and knowing.

All of these approaches can be successful if the participants are engaged and dedicated to the goal of the experience. How would your board game experience change if first you participated in a 30 minute structured dialogue that asked participants to share a story around the prompt like “Please share a time when you knew you belonged in a community”? How would your gaming experiences change you if heard a fellow gamer’s story about a moment when they realized they just did not fit within a community?

There are numerous other approaches that could be considered too, any of which could be specifically tailored to working in the board game community and could be well worth it to consider in making our community less compartmentalized.

For me, I think getting to know my fellow gamers on a deeper level has a huge potential for creating a greater gaming experience. Would you be game to get to know the folks in your community better? Would you be interested in participating in intentional community building at a convention or other gaming meet up? I would be and I am hoping you would be too.

![]()

Brendon Soltis is a contributing writer and an avid fan of the idea that greater understanding can be fostered through gaming. He can be best reached via Twitter.

Feel free to share your thoughts with us over on our social media pages!

Photo Credits: Microphone by Kian McKellar; Chat by Neil Schofield; Group Chat by Deb Nystrom; Gorilla by Steven Straiton