The ABCs of GMing

The ABCs of GMing

The ABCs of GMing is an ongoing series about the different skills and ideas needed to run a successful tabletop game.

Hard Work

Earlier in this series, we discussed the level of Dedication it takes to be a GM. We looked at the ideas of planning ahead of your players, investing the necessary time developing your game, the inclusion of your players and their characters into your crafted story, and the importance of being reliable and consistent with your game sessions. In this segment on Hard Work, we’re going to expand on these ideas and look at some of the more detailed steps to take along the same lines as Dedication. Some of our focus will be on the “Smarter Not Harder” mentality of your work load, but since “S”, as you’ll see, is already assigned to another trait, we’ll slip some in here for good measure.

Study Your System

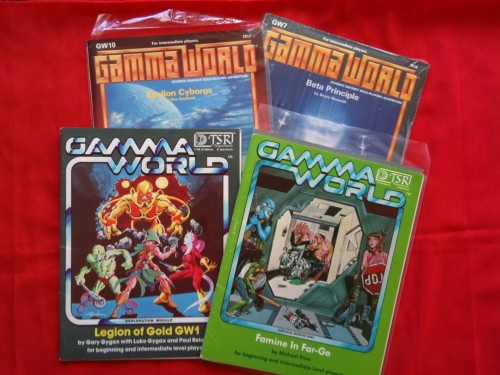

Even if you plan to run a pre-written module campaign, it doesn’t mean you simply can unwrap the book and run with it the vast majority of the time. The core concepts of your system are just as important as the story your characters are playing through, regardless of whether it’s something you’ve created or not.

To that end, it cannot be stressed enough the importance on knowing the system you are running. It’s important that you have a basic understanding of all the rules, classes, races, skills, attributes, and multitude of other statistics and figures for the world you are playing in even before your players make their characters. You don’t have to know everything, but familiarize yourself with the basics. Once your players have created their characters, review them; go back to your sourcebooks to expand your knowledge of the system that is relative to their characters.

After running a few games in your platform, you’ll get the hang of things, and a lot of this information will be easy to recall. However if it’s your first or second time running an entirely alien game system, study the core rulebook like you’re in school. You will be the teacher the other players look to, regardless of the other player’s experience with the game, so be prepared as such. Give yourself ample time to learn what you need to know before you jump headfirst into a game.

The Session Doesn’t End When Your Players Leave

Wrapping up a six-hour game session can be a rewarding experience, and it’ll likely be a relief to all parties involved. However, your job as a GM doesn’t stop there. Shortly after the game (or after a good night’s rest for those late-night gamers), consolidate your notes on how the session went. (Also, take notes during the session if you aren’t doing so already). Collect information on what your players did, how far along your storyline they progressed, and highlight actions and decisions that may alter the way your story carries out. Similar to the example regarding surprise combat tactics mentioned in Generosity, players can easily make decisions and influence NPCs in such a manner that your story may take an unexpected turn or twelve.

With solid notes from an accurate review of a session’s developments, you’ll be able to take this information and apply it to your story so that you don’t get entirely derailed somewhere down the line. Additionally, look at how much progress your characters have made, and develop your story further, in order to keep yourself ahead of your players. While you’re just as likely to have your own schedule conflicts and restrictions as your players, it’s important to keep on top of these things as best you can. Failure to keep yourself up-to-date on your game sessions will impede the storyline, and suddenly you’ll find yourself having to make major campaign plot points on the fly.

Become an Encyclopedia (Or Make One)

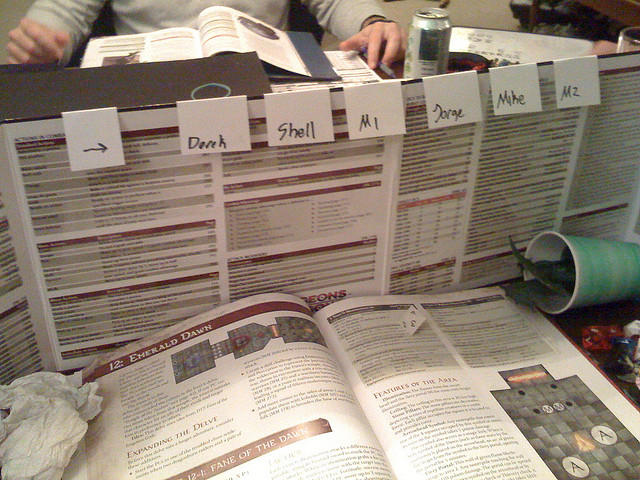

RPG source books can be huge, let alone the copious amounts of supplement material each system can carry. No one can stay entirely on top of all that game knowledge (short of working on tabletops for a living), but you need to know where to look. Part of this “smarter-not-harder” model is knowing exactly where common rules or statistics are listed. Some systems are generous, providing the means to aid with this, usually as added products.

For example, GM screens normally have this information listed and are a huge help running a campaign. However, even these tools cannot cover everything, and they can’t accommodate for special rules that may apply to your players due to class, race, skill, etc. One option is to study and memorize the approximations of where thing are. You don’t need to know that the rules for melee combat are exactly on page 273, but knowing that they are ‘in Chapter Four of the core book, about 12 pages in’ can be much more helpful than you may think. Additionally, knowing that approximation eventually leads to knowing the exact page number. (This is how veteran GMs do it.) If this seems like something you may not be up to doing, then make a cheat sheet and organize it in whatever manner makes sense to you.

The goal is so you can easily refer to your personalize guidebook when you need to check a rule or ability, without having to scour the indexes of multiple source books trying to find the answer. A tip to help with this: ask your players to denote book and page numbers on their character sheets when they take special abilities or acquire special gear. That way, when you look at them like they’re talking Klingon long into the campaign and you’ve forgotten (it’ll happen), they can tell you the book and page number for the information you need. Besides, what’s smarter than effectively getting your players to track all the crazy things they are doing for you?

Dedication

While there is already a full segment solely for this trait, it really bears mentioning again. Running a game is not something you can casually do on the fly. Okay, you can, but it’ll go poorly and your players are the ones who will suffer. You have to commit yourself to it, and give it the time it deserves. Think of it as a part time job where you get to make your own schedule. The more time you schedule yourself at a job, the more money you make. Schedule yourself for less time, and paying the bills and rent becomes difficult. The same holds true as a GM. The more time you spend on your game, the more fun and enjoyment everyone at the table will have. When you start neglecting the upkeep that it takes to maintain a game, it begins to show. Invest in your game and the payback is that you’ll have much more fun – and your players will too.

Next time, I’ll be talking about Improvisation (a personal favorite of my theater geek alter ego), reviewing how a GM can keep him or herself on their toes and look like a genius in the process. In the meantime, feel free to tell us about your own tales of generosity on our social media pages!

Photo Credits: Gamma World Modules by Atomicmom; GM Screen by Mike Shea.